Dangerous javascript: pseudo protocol

In the previous post, various XSS scenarios and ways to execute code were mentioned, including something called the javascript: pseudo protocol. Even from a modern frontend perspective, this is something that developers need to be particularly aware of.

Therefore, it is worth writing a dedicated post to discuss it in detail.

Before we begin, let's answer the brainstorming question from the previous post. In the injection point of innerHTML, <script> tags are not executed. However, they can be used in conjunction with iframes.

The srcdoc attribute of an iframe can contain complete HTML, creating a whole new webpage. So, the <script> tag that was previously useless can be used here. Additionally, since it is an attribute, the content can be encoded beforehand, meaning the result is the same:

document.body.innerHTML =

'<iframe srcdoc="<script>alert(1)</script>"></iframe>';

Therefore, even if the injection point is innerHTML, <iframe srcdoc> along with <script> can be used to execute code.

Now let's move on to the main topic of this post: "javascript: pseudo protocol".

What is the javascript: pseudo protocol?

The word "pseudo" refers to pseudo code, which is like a virtual code.

Compared to "real protocols" like HTTP, HTTPS, or FTP, the pseudo protocol is more like a special protocol unrelated to the network. Examples of pseudo protocols include mailto: and tel:.

The reason why the javascript: pseudo protocol is special is that it can be used to execute JavaScript code.

Where can the javascript: pseudo protocol be used?

The first place is the href attribute mentioned in the previous post:

<a href="javascript:alert(1)">Link</a>

Simply clicking on this link triggers an XSS attack.

The second place is the src attribute of <iframe>:

<iframe src="javascript:alert(1)"></iframe>

Unlike the <a> example, this does not require any user interaction to trigger.

Lastly, the action attribute of <form> can also contain the same thing. The formaction attribute of <button> is also similar, but both of these, like <a>, require a click to trigger:

<form action="javascript:alert(1)">

<button>submit</button>

</form>

<form id="f2"></form>

<button form="f2" formaction="javascript:alert(2)">submit</button>

Why is it dangerous?

It is often overlooked and frequently used in practical applications.

For example, if a website has a feature that allows users to input a YouTube video URL and automatically embed it in an article, and the developer of this feature lacks security awareness, they might write it like this:

<iframe src="<?= $youtube_url ?>" width="500" height="300"></iframe>

If I input javascript:alert(1) as the YouTube URL, it becomes an XSS vulnerability. Even if a check is added to verify if the URL contains youtube.com, it can be bypassed using javascript:alert(1);console.log('youtube.com').

The correct approach is to check if the URL is in the format of a YouTube video and ensure that the URL starts with https://.

If you think the above feature is not very common, try inputting your own blog or Facebook URL on a profile page and adding a hyperlink to the page. This feature becomes more common, right?

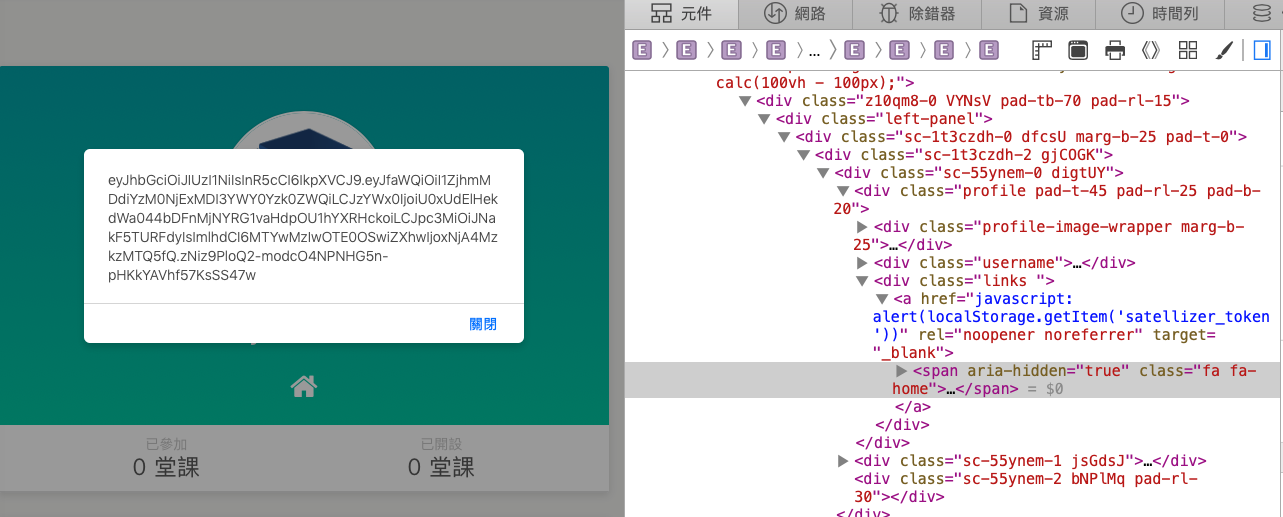

This is an easily overlooked area. I myself discovered this vulnerability in Hahow, an online course platform in Taiwan:

If the backend implementation is written as code, it would look something like this:

<a href="<?php echo htmlspecialchars($data) ?>">link</a>`

Even though <>" are encoded, preventing the addition of tags and escaping double quotes to add attributes, an attacker can still inject javascript:alert(1) because there are no illegal characters in it.

Furthermore, modern frontend frameworks usually handle escaping automatically. If you are not using dangerouslySetInnerHTML in React or v-html in Vue, there shouldn't be any issues. However, href is different for the reasons mentioned above; its content is not sanitized.

Therefore, if you write like this in React, it will cause issues:

import React from "react";

export function App(props) {

// Assume the following data comes from the user input

const href = "javascript:alert(1)";

return <a href={href}>click me</a>;

}

This is an XSS vulnerability, where executing code is just a click away.

However, React introduced a warning for this behavior in v16.9, and it is also documented: Deprecating javascript: URLs. The warning message states:

Warning: A future version of React will block javascript: URLs as a security precaution. Use event handlers instead if you can. If you need to generate unsafe HTML try using dangerouslySetInnerHTML instead.

There is also more discussion on this topic in React's GitHub issues:

- React@16.9 block javascript:void(0); #16592

- False-positive security precaution warning (javascript: URLs) #16382

On the other hand, in Vue, you can write like this:

<script setup>

import { ref } from 'vue'

const link = ref('javascript:alert(1)')

</script>

<template>

<a :href="link">click me</a>

</template>

This will also successfully execute JavaScript. This attack method is mentioned in Vue's documentation, called URL Injection. It is recommended that developers handle URL validation and processing on the backend rather than waiting until the frontend.

If you need to handle it on the frontend, it is suggested to use the sanitize-url library.

Page redirection also carries risks

Many websites implement a "redirect after login" feature, which redirects users to the originally intended page before logging in, like this:

const searchParams = new URLSearchParams(location.search);

window.location = searchParams.get("redirect");

So, what's the problem with this code?

The problem is that the value of window.location can also be a javascript: pseudo-protocol!

window.location = "javascript:alert(document.domain)";

After executing the above code, you will see a familiar alert window. This is something frontend engineers need to be aware of. As I mentioned earlier, redirecting is a common functionality, and when implementing it, you must be cautious about this issue to avoid writing problematic code.

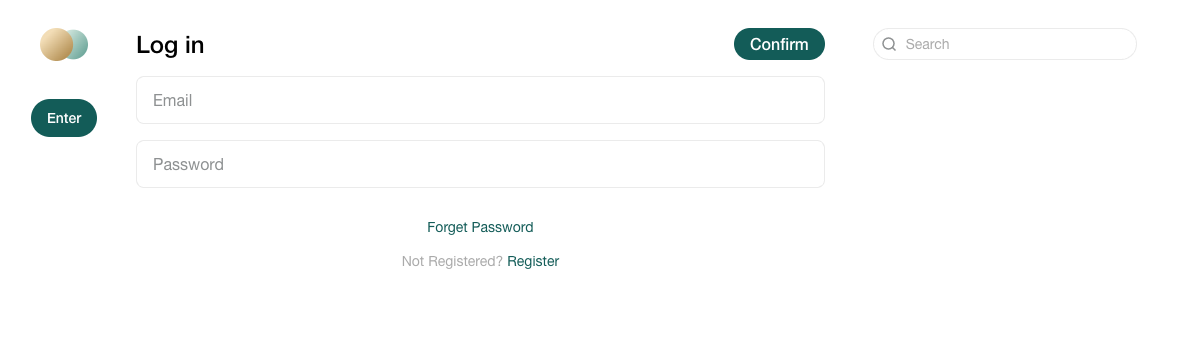

I actually discovered this vulnerability on another website called Matters News. This is their login page:

After clicking the confirm button, a function called redirectToTarget is called, and the code for this function is as follows:

/**

* Redirect to "?target=" or fallback URL with page reload.

*

* (works on CSR)

*/

export const redirectToTarget = ({

fallback = "current",

}: {

fallback?: "homepage" | "current",

} = {}) => {

const fallbackTarget =

fallback === "homepage"

? `/` // FIXME: to purge cache

: window.location.href;

const target = getTarget() || fallbackTarget;

window.location.href = decodeURIComponent(target);

};

After obtaining the target, it directly uses: window.location.href = decodeURIComponent(target) for redirection. And getTarget simply retrieves the value of the target from the query string. So, if the login URL is: https://matters.news/login?target=javascript:alert(1), when the user clicks login and is successful, an alert will pop up, triggering XSS!

Moreover, once this XSS is triggered, its impact is significant because it occurs on the login page. Therefore, the XSS executed on this page can directly capture the input values, which means stealing the user's username and password. To carry out an actual attack, phishing emails can be sent to the website's users, including this malicious link for them to click. Since the URL appears normal and the resulting page is also the genuine website page, the credibility should be quite high.

By stealing the username and password through XSS after the user enters them and logs in, and redirecting the user back to the homepage without leaving any traces, the user's account can be compromised, achieving account takeover.

In short, I believe everyone is familiar with the basic concept of XSS. However, you may not be as familiar with the attack surface of the javascript: pseudo-protocol. Therefore, I would like to specifically address this issue so that you can be more cautious and take appropriate defensive measures when encountering such attributes.

Defense Methods

Firstly, if you have libraries like sanitize-url mentioned above, that would be ideal. Although it may not be completely risk-free, it is widely used and has undergone extensive testing, so many issues and bypass methods may have already been addressed.

Do you want to handle it yourself? It is possible, but let's see what usually happens when you handle it on your own.

Since the attack string is javascript:alert(1), some may think that checking if it starts with javascript: or removing all instances of javascript from the string would be sufficient.

However, this approach is not effective because it is the content of the href attribute, and the attribute content in HTML can be encoded. In other words, I can do this:

<a href="javascript:alert(1)">click me</a>

Inside, there is no content that we want to filter, and it does not start with javascript:, so it can bypass the restriction.

A better approach is to only allow strings that start with http:// or https://. This will generally prevent any issues. Some more rigorous methods involve using JavaScript to parse the URL, like this:

console.log(new URL("javascript:alert(1)"));

/*

{

// ...

href: "javascript:alert(1)",

origin: "null",

pathname: "alert(1)",

protocol: "javascript:",

}

*/

This way, you can determine if the protocol is valid based on the protocol and block any content not on the allow-list.

Another common mistake is to use URL parsing based on the hostname or origin, like this:

console.log(new URL("javascript:alert(1)"));

/*

{

// ...

hostname: "",

host: "",

origin: null

}

*/

When hostname or host is empty, it means it is an invalid URL. Although this method may seem fine at first glance, we can use the feature in JavaScript where // is treated as a comment, combined with newline characters, to create a string that looks like a URL but is actually a javascript: pseudo-protocol:

console.log(new URL("javascript://huli.tw/%0aalert(1)"));

/*

{

// ...

hostname: "",

host: "",

origin: null

}

*/

Although it looks like a URL, it works fine in Chrome without any issues or false positives. However, Safari behaves differently. When executing the same code in Safari 16.3, the output is:

console.log(new URL("javascript://huli.tw/%0aalert(1)"));

/*

{

// ...

hostname: "huli.tw",

host: "huli.tw",

origin: "null"

}

*/

In Safari, it successfully parses the hostname and host. By the way, I learned this trick from Masato's tweet.

If you really want to use RegExp to check if it is a javascript: pseudo-protocol, you can refer to the implementation in React's source code (many libraries use a similar RegExp):

// A javascript: URL can contain leading C0 control or \u0020 SPACE,

// and any newline or tab are filtered out as if they're not part of the URL.

// https://url.spec.whatwg.org/#url-parsing

// Tab or newline are defined as \r\n\t:

// https://infra.spec.whatwg.org/#ascii-tab-or-newline

// A C0 control is a code point in the range \u0000 NULL to \u001F

// INFORMATION SEPARATOR ONE, inclusive:

// https://infra.spec.whatwg.org/#c0-control-or-space

/* eslint-disable max-len */

const isJavaScriptProtocol =

/^[\u0000-\u001F ]*j[\r\n\t]*a[\r\n\t]*v[\r\n\t]*a[\r\n\t]*s[\r\n\t]*c[\r\n\t]*r[\r\n\t]*i[\r\n\t]*p[\r\n\t]*t[\r\n\t]*\:/i;

From this regular expression, you can see the flexibility of javascript:. It can have additional characters before the start and even an unlimited number of newlines and tabs within the string. This is why I mentioned that it is difficult to handle it on your own because you need to be familiar with the specification to understand these behaviors.

In addition to the methods mentioned above, simply adding target="_blank" can have a significant effect because many browsers have already addressed this issue.

In Chrome, when you click on the link, it opens a new tab with the URL about:blank#blocked. In Firefox, it opens a new tab without a URL. In Safari, nothing happens. None of these desktop browsers execute JavaScript.

The tested versions are Chrome 115, Firefox 116, and Safari 16.3.

In the real world, most links do have the target="_blank" attribute.

However, if the user clicks on the link with the middle mouse button instead of the left mouse button, the situation may be different. Therefore, regardless of the situation, the root cause should be fixed instead of relying on browser protections.

For more details, you can refer to The curious case of XSS and the mouse middle button. and Anchor Tag XSS Exploitation in Firefox with Target="_blank".

Practical Case

Let's take a look at a vulnerability discovered in the Telegram web version not long ago (June 2023). It is related to the javascript: pseudo-protocol and was mentioned in Slonser's article История одной XSS в Telegram (in Russian).

In Telegram Web A (Telegram has more than one web version), there is a function called ensureProtocol that is responsible for checking if a URL has ://. If it doesn't, it automatically adds http://:

export function ensureProtocol(url?: string) {

if (!url) {

return undefined;

}

return url.includes("://") ? url : `http://${url}`;

}

It is easy to bypass this check by using something like javascript:alert('://'). This allows the successful use of the javascript: pseudo-protocol. However, the issue is that the server also checks if the URL is a valid address, and the previous string clearly isn't.

URLs can include a username and password at the beginning (used for HTTP Authentication), separated by a colon (:), like this:

https://username:password@www.example.com/

Therefore, Slonser discovered that this string can be used to bypass the check:

javascript:alert@github.com/#://

In this case, javascript is the username, alert is the password, and the hostname is github.com. Although it doesn't start with http:// or https://, the server still considers it a valid URL.

Finally, by combining URL encoding, a URL is generated with a password that only contains valid characters:

javascript:alert%28%27Slonser%20was%20here%21%27%29%3B%2F%2F@github.com#;alert(10);://eow5kas78d0wlv0.m.pipedream.net%27

// after decoded

javascript:alert('Slonser was here!');//@github.com#;alert(10);://eow5kas78d0wlv0.m.pipedream.net'

The server recognizes the above string as a link, and the client can bypass the :// check. When a user clicks on this link, an XSS attack is triggered.

Telegram later fixed this issue by implementing the method I mentioned earlier, which checks the URL and ensures that the protocol is not javascript:. Link: Fix protocol verification (#3417):

export function ensureProtocol(url?: string) {

if (!url) {

return undefined;

}

// HTTP was chosen by default as a fix for https://bugs.telegram.org/c/10712.

// It is also the default protocol in the official TDesktop client.

try {

const parsedUrl = new URL(url);

// eslint-disable-next-line no-script-url

if (parsedUrl.protocol === "javascript:") {

return `http://${url}`;

}

return url;

} catch (err) {

return `http://${url}`;

}

}

Conclusion

In this article, we have seen the dangerous aspects of the javascript: pseudo-protocol. It can be placed inside the href attribute of an <a> tag, which is a common use case. Additionally, developers often forget about the potential risks or may not be aware of them, leading to vulnerabilities.

Although in most cases, hyperlinks open in new tabs, preventing the execution of JavaScript code, there is no guarantee that behavior is consistent everywhere (e.g., when target attribute is not specified) or when using older browsers or alternative methods to open new tabs. This poses a risk to users.

Furthermore, when performing redirects, it is important to consider the issues related to the javascript: pseudo-protocol. Without proper prevention, it can lead to an XSS vulnerability.

As developers, it is crucial to be constantly aware of these issues and handle them appropriately in the code, as stated in the famous quote:

Never trust user input.

Lastly, I leave a small question for everyone: What is the problem with the following code? It doesn't necessarily have to be an XSS vulnerability; any security-related issue counts:

// This is a feature that users can embed their favorite YouTube videos in their profile page

const url = "value from user";

// Make sure it's YouTube video URL

if (url.startsWith("https://www.youtube.com/watch")) {

document.querySelector("iframe").src = url;

}