The Second Line of Defense Against XSS: CSP

The first line of defense against XSS is to sanitize user input and ensure that the content is safe. However, it is easier said than done, especially for legacy projects with messy and complex code. It becomes difficult to determine where to make the necessary fixes.

Furthermore, mistakes can happen while writing code, and there are three main reasons for security issues:

- You are unaware that certain actions can lead to problems.

- You forget that certain actions can lead to problems.

- You are aware that certain actions can lead to problems, but due to project deadlines or instructions from superiors, you choose to ignore them.

The first reason is similar to the example mentioned earlier with the <a href> tag, where you may not be aware that it can execute code using javascript:.

The second reason is when you are aware of XSS vulnerabilities and know that output should be encoded, but you forget to do so.

The third reason is when you knowingly leave a vulnerability unencoded, even though it should be encoded, due to project time constraints or instructions from superiors.

In the case of the first reason, where you have no idea where to handle the issue or that there is a vulnerability, how can you defend against it? This is why we need the second line of defense.

Automatic Defense Mechanism: Content Security Policy

CSP, short for Content Security Policy, allows you to establish rules for your web page and inform the browser that only content that adheres to these rules should be allowed. Any content that does not comply should be blocked.

There are two ways to add CSP to a web page. One is through the HTTP response header Content-Security-Policy, and the other is through the <meta> tag. Since the latter is easier to demonstrate, we will focus on that (although the former is more commonly used, as some rules can only be set through it).

(There is also a mysterious third method involving the csp attribute of <iframe>, but that is a different topic that we won't discuss here.)

Let's look at an example:

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<head>

<meta http-equiv="Content-Security-Policy" content="script-src 'none'">

</head>

<body>

<script>alert(1)</script>

CSP test

</body>

</html>

In the above web page, CSP is declared as script-src 'none', which means "no script execution is allowed" on this web page. Therefore, the script in the body will not be executed. If you open the DevTools, you will see the following error message:

Refused to execute inline script because it violates the following Content Security Policy directive: "script-src 'none'". Either the 'unsafe-inline' keyword, a hash ('sha256-bhHHL3z2vDgxUt0W3dWQOrprscmda2Y5pLsLg4GF+pI='), or a nonce ('nonce-...') is required to enable inline execution.

This is why I refer to CSP as the second line of defense. When your first line of defense (handling user input) fails, you can still rely on CSP to prevent the loading of scripts or other resources, effectively preventing XSS vulnerabilities.

Rules of CSP

CSP allows you to define directives along with rules. In the example above, the directive script-src is set to 'none', which ultimately blocks the execution of any JavaScript.

First, it's important to note that the directive script-src should not be easily interpreted as "the src attribute of script tags." Here, the term "script" refers to general "scripts" and not specifically to script tags or src attributes.

For example, if there is an HTML snippet <a href="javascript:alert(1)">click</a> on the page, which does not have a script tag or src attribute, it will still be blocked by CSP, and an error message will be displayed. This is because script-src 'none' means "block the execution of any JavaScript," whether it is through script tags, event handlers, or the javascript: pseudo-protocol.

So, what are the available directives?

The most important one is default-src, which represents the default rules. For example, if script-src is not set, the rules from default-src will be used. However, it's important to note that some directives do not fallback to default-src, such as base-uri or form-action. You can find the complete list here: The default-src Directive

Other commonly used directives include:

script-src: Manages JavaScriptstyle-src: Manages CSSfont-src: Manages fontsimg-src: Manages imagesconnect-src: Manages connections (fetch, XMLHttpRequest, WebSocket, etc.)media-src: Manages videos and audiosframe-src: Manages frames and iframesbase-uri: Manages the use of<base>form-action: Manages form actionsframe-ancestors: Manages which pages can embed the current pagereport-uri: To be discussed laternavigate-to: Manages where the page can navigate to

There are many types, right? And this list is subject to change. For example, the navigate-to at the end is a newer feature that is not yet supported by current browsers.

In addition to these, there are actually many more, but I didn't specifically mention the less commonly used ones. If you're interested, you can refer to MDN: Content-Security-Policy or Content Security Policy Reference for more information.

So, what are the possible rules for each of these? Depending on the directives, different rules can be used.

The commonly used rules are as follows:

*- Allows all URLs exceptdata:,blob:, andfilesystem:.'none'- Doesn't allow anything.'self'- Only allows same-origin resources.https:- Allows all HTTPS resources.example.com- Allows specific domains (both HTTP and HTTPS).https://example.com- Allows specific origins (HTTPS only).

For example, script-src * is basically equivalent to not setting any rule(allows all URLs, but it's worth noting that inline script is still blocked), while script-src 'none' completely blocks the execution of any JavaScript.

Furthermore, some rules can be combined. In practice, you often see rules like this:

script-src 'self' cdn.example.com www.google-analytics.com *.facebook.net

Sometimes scripts are hosted on the same origin, so self is needed. Some scripts are hosted on a CDN, so cdn.example.com is required. And because Google Analytics and Facebook SDK are used, www.google-analytics.com *.facebook.net is needed to load their JavaScript.

The complete CSP is a combination of these rules, with directives separated by ;, like this:

default-src 'none'; script-src 'self' cdn.example.com www.google-analytics.com *.facebook.net; img-src *;

Through CSP, we can inform the browser which resources are allowed to be loaded and which are not. Even if an attacker finds an injection point, they may not be able to execute JavaScript, thus mitigating the impact of an XSS vulnerability (although it still needs to be fixed, but the risk is smaller).

Rules for script-src

In addition to specifying the URLs of the resources to be loaded, there are other rules that can be used.

For example, after setting CSP, inline scripts and eval are blocked by default. The following inline scripts are blocked:

- Code directly placed inside

<script>tags (should be loaded from an external source using<script src>) - Event handlers written in HTML, such as

onclick - The

javascript:pseudo-protocol

To allow the use of inline scripts, the 'unsafe-inline' rule needs to be added.

And if you want to execute code as if it were eval, you need to add the 'unsafe-eval' rule. Some people may know that setTimeout can also execute code as a string, like this:

setTimeout('alert(1)')

Similarly, setInterval, Function, and others can achieve the same thing, but they all require the 'unsafe-eval' rule to be used.

In addition to these, there is also 'nonce-xxx', which means generating a random string on the backend, for example, a2b5zsa19c. Then, a script tag with nonce=a2b5zsa19c can be loaded:

<!-- Allowed -->

<script nonce=a2b5zsa19c>

alert(1)

</script>

<!-- Not allowed -->

<script>

alert(1)

</script>

There is also a similar 'sha256-abc...' rule, which allows specific inline scripts based on their hash. For example, if we take alert(1) and calculate its sha256 hash, we get a binary value that, when base64 encoded, becomes bhHHL3z2vDgxUt0W3dWQOrprscmda2Y5pLsLg4GF+pI=. Therefore, in the example below, only the script with the exact content of alert(1) will be loaded, while others will not be loaded:

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<head>

<meta http-equiv="Content-Security-Policy" content="script-src 'sha256-bhHHL3z2vDgxUt0W3dWQOrprscmda2Y5pLsLg4GF+pI='">

</head>

<body>

<!-- Allowed -->

<script>alert(1)</script>

<!-- Not Allowed -->

<script>alert(2)</script>

<!-- An extra space is also not allowed because it results in a different hash value-->

<script>alert(1) </script>

</body>

</html>

Finally, there is one more that may be used, 'strict-dynamic', which means: "Scripts that comply with the rules can load other scripts without being restricted by CSP." Like this:

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<head>

<meta http-equiv="Content-Security-Policy" content="script-src 'nonce-rjg103rj1298e' 'strict-dynamic'">

</head>

<body>

<script nonce=rjg103rj1298e>

const element = document.createElement('script')

element.src = 'https://example.com'

document.body.appendChild(element)

</script>

</body>

</html>

In the CSP we set, only nonce-rjg103rj1298e is allowed for scripts, and no other sources are allowed. However, scripts added from within <script nonce=rjg103rj1298e> are not restricted and can dynamically add scripts from other sources. This is the function of 'strict-dynamic'.

How to determine the CSP rules?

When setting up CSP, it usually starts with default-src 'self', allowing same-origin resources by default.

Next, let's handle the most important scripts. Usually, the top priority is to avoid using 'unsafe-inline' and 'unsafe-eval', as having these two doesn't make much difference compared to not having CSP at all.

What is the purpose of adding CSP? It is to serve as the second line of defense against XSS attacks. However, if 'unsafe-inline' is added, it undermines this defense line, as simply inserting <svg onload=alert(1)> can execute code.

But in reality, there are usually some existing inline scripts that force us to add unsafe-inline. Here, I will introduce a common approach. For example, with Google Analytics, they will ask you to add the following code to your webpage:

<script async src="https://www.googletagmanager.com/gtag/js?id=UA-XXXXXXXX-X"></script>

<script>

window.dataLayer = window.dataLayer || [];

function gtag(){dataLayer.push(arguments);}

gtag('js', new Date());

gtag('config', 'UA-XXXXXXXX-X');

</script>

This is the inline script we want to avoid. So, what can we do? The official documentation provided by Google, Using a code management tool with Content Security Policy, mentions two solutions:

- Add a nonce to that specific script.

- Calculate the hash of that script and add a rule like

sha256-xxx.

Both of these solutions allow specific inline scripts to execute without relying on the wide-open permission of 'unsafe-inline'. In addition, the official documentation also reminds us that if we want to use the "Custom JavaScript Variable" feature, we must enable 'unsafe-eval' for it to work.

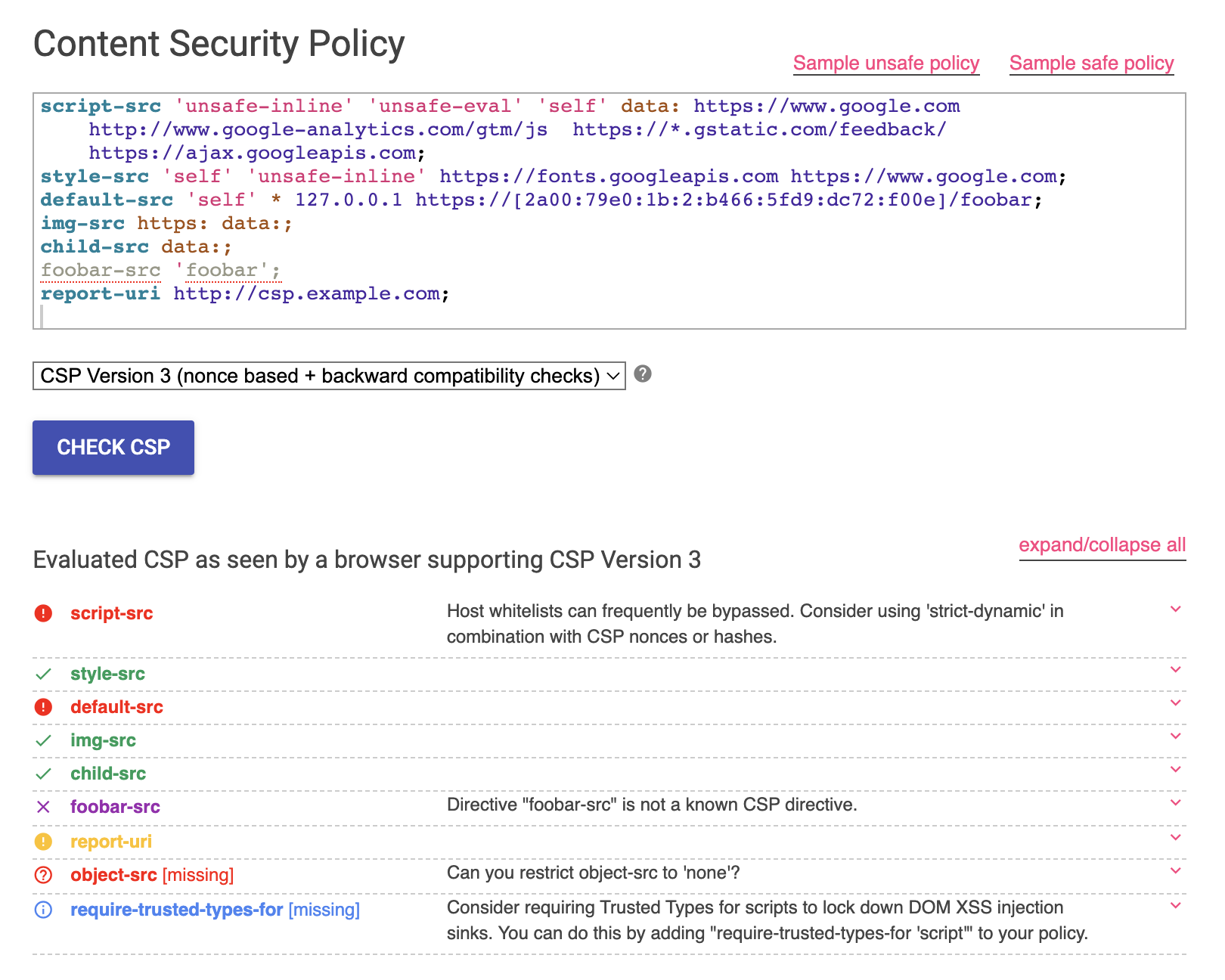

If you are unsure whether your CSP is secure, you can use a website provided by Google called CSP Evaluator. It will detect any errors in your CSP and evaluate its security, as shown in the following image:

Although it was mentioned earlier that a poorly configured CSP is similar to not having one at all, it is still better to have a configuration. After all, taking the first step is important. Many companies may not have known about CSP in the past, so adding it is commendable, and improvements can be made gradually.

In the first half of the article, there was a mention of a directive called "report-uri," which is a very considerate feature. If CSP is not properly configured, it can potentially block normal resources, causing the website to malfunction or certain features to break. This would be a loss.

Therefore, there is another header called Content-Security-Policy-Report-Only, which means you can set CSP but it won't actually block anything. Instead, it will send a report to a specified URL when a resource that violates the rules is loaded.

With this feature, we can observe any violations of CSP and check if there are any misconfigurations by examining the logs. Once everything is confirmed to be fine, we can switch to using Content-Security-Policy.

How do others configure their CSP?

Have you ever seen a long string of CSP?

Let's take a look at the CSP on the GitHub homepage to get a sense of what a long string looks like:

default-src

'none';

base-uri

'self';

child-src

github.com/assets-cdn/worker/

gist.github.com/assets-cdn/worker/;

connect-src

'self'

uploads.github.com

objects-origin.githubusercontent.com

www.githubstatus.com

collector.github.com

raw.githubusercontent.com

api.github.com

github-cloud.s3.amazonaws.com

github-production-repository-file-5c1aeb.s3.amazonaws.com

github-production-upload-manifest-file-7fdce7.s3.amazonaws.com

github-production-user-asset-6210df.s3.amazonaws.com

cdn.optimizely.com

logx.optimizely.com/v1/events

*.actions.githubusercontent.com

productionresultssa0.blob.core.windows.net/

productionresultssa1.blob.core.windows.net/

productionresultssa2.blob.core.windows.net/

productionresultssa3.blob.core.windows.net/

productionresultssa4.blob.core.windows.net/

wss://*.actions.githubusercontent.com

github-production-repository-image-32fea6.s3.amazonaws.com

github-production-release-asset-2e65be.s3.amazonaws.com

insights.github.com

wss://alive.github.com github.githubassets.com;

font-src

github.githubassets.com;

form-action

'self'

github.com

gist.github.com

objects-origin.githubusercontent.com;

frame-ancestors

'none';

frame-src

viewscreen.githubusercontent.com

notebooks.githubusercontent.com;

img-src

'self'

data:

github.githubassets.com

media.githubusercontent.com

camo.githubusercontent.com

identicons.github.com

avatars.githubusercontent.com

github-cloud.s3.amazonaws.com

objects.githubusercontent.com

objects-origin.githubusercontent.com

secured-user-images.githubusercontent.com/

user-images.githubusercontent.com/

private-user-images.githubusercontent.com

opengraph.githubassets.com

github-production-user-asset-6210df.s3.amazonaws.com

customer-stories-feed.github.com

spotlights-feed.github.com

*.githubusercontent.com;

manifest-src

'self';

media-src

github.com

user-images.githubusercontent.com/

secured-user-images.githubusercontent.com/

private-user-images.githubusercontent.com

github.githubassets.com;

script-src

github.githubassets.com;

style-src

'unsafe-inline'

github.githubassets.com;

upgrade-insecure-requests;

worker-src

github.com/assets-cdn/worker/

gist.github.com/assets-cdn/worker/

Basically, it includes various possible configurations. As for the scripts we are most concerned about, only github.githubassets.com; is allowed, which is a secure way of configuring it.

GitHub's bug bounty program also has a special category called GitHub CSP. If you can bypass CSP and execute code, even if you haven't found a place to inject HTML, it still counts.

Now let's look at Facebook:

default-src

*

data:

blob:

'self'

'wasm-unsafe-eval'

script-src

*.facebook.com

*.fbcdn.net

*.facebook.net

*.google-analytics.com

*.google.com

127.0.0.1:*

'unsafe-inline'

blob:

data:

'self'

'wasm-unsafe-eval'

style-src

data:

blob:

'unsafe-inline'

*

connect-src

secure.facebook.com

dashi.facebook.com

dashi-pc.facebook.com

graph-video.facebook.com

streaming-graph.facebook.com

z-m-graph.facebook.com

z-p3-graph.facebook.com

z-p4-graph.facebook.com

rupload.facebook.com

upload.facebook.com

vupload-edge.facebook.com

vupload2.facebook.com

z-p3-upload.facebook.com

z-upload.facebook.com

graph.facebook.com

'self'

*.fbcdn.net

wss://*.fbcdn.net

attachment.fbsbx.com

blob:

data:

*.cdninstagram.com

*.up.facebook.com

wss://edge-chat-latest.facebook.com

wss://edge-chat.facebook.com

edge-chat.facebook.com

edge-chat-latest.facebook.com

wss://gateway.facebook.com

*.facebook.com/rsrc.php/

https://api.mapbox.com

https://*.tiles.mapbox.com

block-all-mixed-content

upgrade-insecure-requests;

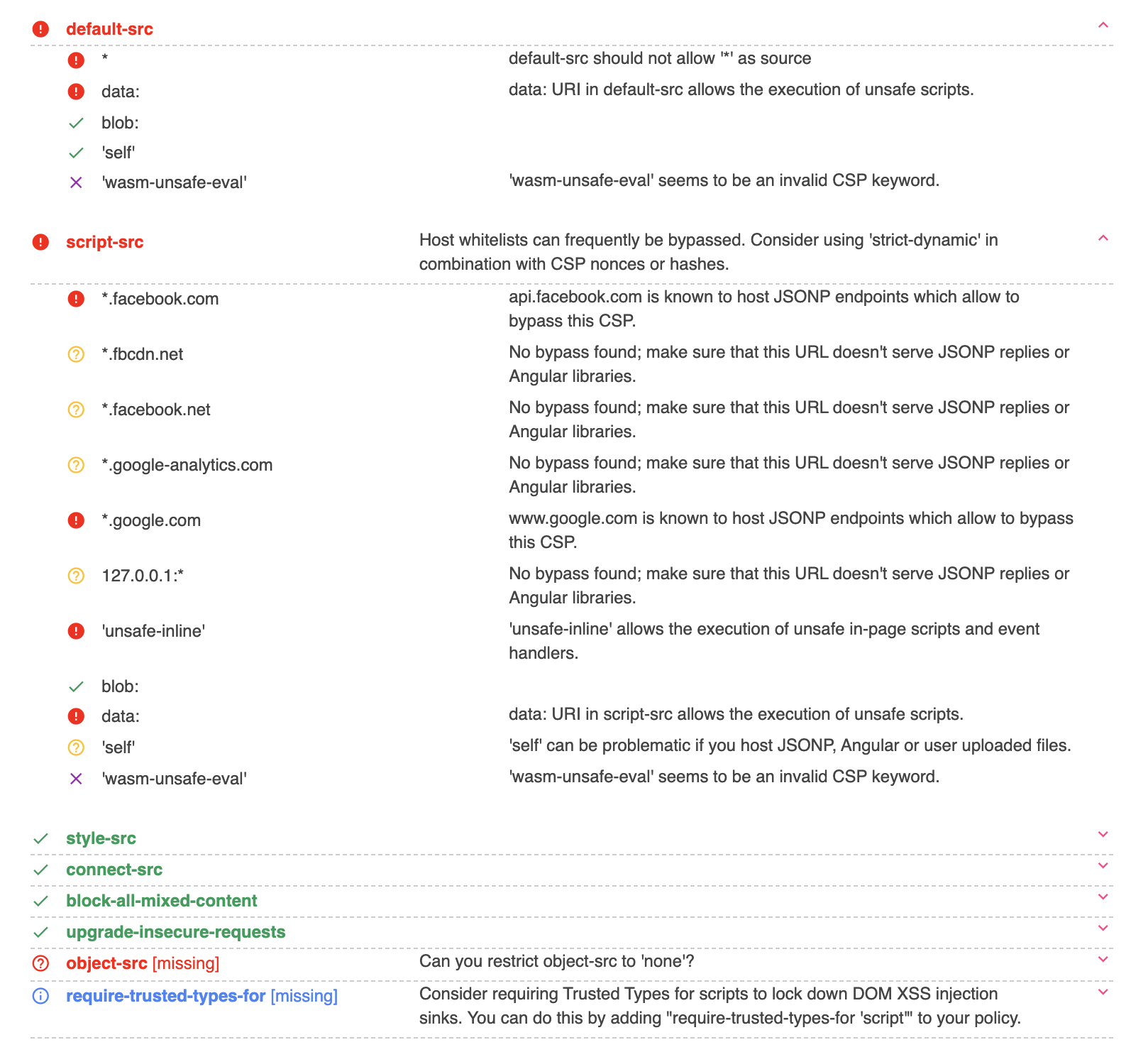

Although it is also a long string, you can notice that 'unsafe-inline' is enabled for scripts, which is a less secure approach. If you paste this CSP into the CSP Evaluator mentioned earlier, it will show a lot of red flags:

Conclusion

I personally recommend setting up CSP. Once it is configured, it adds an extra layer of defense, giving us a chance to mitigate any issues. By blocking XSS payloads from attackers through CSP, we can minimize the damage.

Moreover, the barrier to entry is not high. You can start with the "report only" mode, observe and adjust the CSP rules for your website, and make sure it doesn't affect regular users before going live with it.

Finally, let's have a little quiz, which will be answered in future articles.

After reading this article, Bob looked back at his own project and found that all JavaScript files come from https://unpkg.com packages. Therefore, he added the following CSP. What is the problem with the script-src part?

Content-Security-Policy: script-src https://unpkg.com;